|

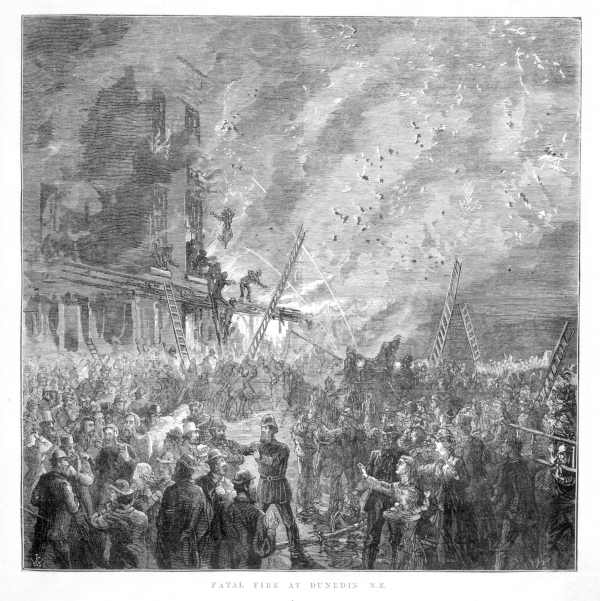

| From the State Library of Victoria, via Wikipedia. |

CALAMITOUS FIRE AT THE OCTAGON.

SERIOUS LOSS OF LIFE,

TWELVE BODIES RECOVERED.

One of the largest and most destructive fires which has occurred in Dunedin for the past few years broke out on Monday morning about half past two o'clock. When the alarm bell tolled out the signal, the fire had a strong hold of the large block of buildings in the Octagon situated next the Athenaeum, and known as Ross's Buildings. The flames were first seen in that portion of the buildings adjoining the dyeworks, at the corner of the Octagon and Stuart street. This was just previous to the arrival of the Brigade. The fire is said to have originated in the Cafe Chantant. Some considerable time elapsed before the Brigade got a hose to bear on the back part of the premises, owing chiefly to the difficulty of access, the only way of leading the hose round from the front being down a narrow right-of-way, and here a stiff fence blocked the way, until an opening could be made through it. When the hose at last began to play, the great height of the building — for the flames were at this time confined to the higher portion — prevented any effective result being attained in that direction. Above the noise, and shouting, and clanging of the bell could be heard the pitiful and heart-rending shrieks of women and men cut off from the only means of exit — the staircase, and it was indeed sorrowful to hear these piercing cries of terror, without any efficient means of rendering assistance. The fire brigade scarcely turned out with their usual promptness, and through the fire-escape having been lately removed from the Masonic Hall a large number of the public who, learning that several lives were in danger rushed round to the Hall for the fire-escape, were debarred from tendering assistance for a time.

The following graphic account of the above distressing calamity appeared in Tuesday mornings Daily Times: —

Yesterday morning we gave a short and hurried account of the very deplorable fire which occurred in the Octagon an hour or two before we went to press. The expectation then formed that a number of lives had been lost has been only too painfully borne out by the facts discovered during yesterday. Ten dead bodies now lie at the Hospital. Nine of these are burnt so badly as to be utterly beyond recognition, and their identity can only be judged from such facts as that they were known to be in the building, and that they were found in rooms where they were known to have been sleeping. One is that of a man who jumped from the building, and died from the injuries he received. At least another body is believed to remain in the ruins, and four persons are also in the Hospital suffering from injuries received in escaping from the flames. Eleven people, therefore, have met death by this terrible catastrophe, and four are more or less injured. The scene of this heartrending occurrence was ROSS' BUILDINGS.

These buildings formed a large brick pile fronting the Octagon, between the corner of Stuart street and the Atheneaum. They belonged to and were built by Mr David, Ross, the well-known architect. They were of four storeys, including a cellar with a back entrance only, but of three storeys from the street line. The cellar was mainly used by a Mr Drysdale, who carried on the business of a drysalter. Fronting and level with the street were three double shops. One — that nearest Stuart street — was occupied by Mr William Waters as a Cafe Chantant, otherwise an eating and boarding-house and a concert room. The centre shop was occupied by Mrs Wilson, who was wife of Mr Robert Wilson, editor of the Otago Witness, and who carried on a millinery and dressmaking business in conjunction with a registry office. The shop at the corner next the Athenaeum was unoccupied. To the first floor a staircase, rising from a main entrance between Mrs Wilson's, and the unoccupied shop, gave access; also a staircase rising from the cafe end of the building; and also by a private staircase from Mrs Wilson's back premises. On this first floor were, over the cafe, rooms used by Mr Waters for the purposes of his business; over this other portion of the building were rooms occupied by various people — one a book-agent, another a music teacher, others by persons who used them as sleeping-rooms, getting their meals about town. A long passage divided these rooms back and front, and was so arranged that a person could come up from the cafe, traverse the passage, and get down into the main street entrance before spoken of without meeting a door. On the second floor the rooms were mainly connected with Mr Waters' cafe; three of those next the Athenaeum were used as sleeping apartments by the Wilson family; one was let by them to two young men and another was used as a spare room for servant girls who were waiting for situations in connection with the registry office. This was the main building. At the back, standing at a kind of angle to the cafe, and approached by a separate entrance from the street, through an archway on the Stuart street side of the cafe, were Mr. Ross' offices. They were unused at present, we believe, Mr Ross being in the Home country. Over the offices were a number of rooms, which were also used by Mr Waters.

THE ORIGIN OF THE FIRE. Very little of a circumstantial nature is known of the origin of the fire. It appears to have been first seen by Mr Hall, of the Dyeworks, which are in Mr Geddes' old building in Stuart street, and by a Miss Simpson, servant to Mr Hall. Mr Hall had been up attending to one of his children, and had lain down again but had not gone to sleep. He was startled by a sudden glare or shoot of flame in what was known in the cafe as the reading-room, situated just behind the stage in the front room. Miss Simpson also saw the glare, and both state that they saw a man pulling the window curtains down, and that, the glare dying away, they imagined the curtains had caught fire and been put out. Very shortly afterwards, however, the flames appeared to break out in the room afresh, and, in no space of time almost, had obtained a powerful hold. Mr Hall (states) this must have taken place about 2 o'clock, or certainly, little after it. He went outside, and called "Fire!" and picking up a brick smashed one of the upper windows in order to alarm the inmates. From the foregoing statement, the fire must have originated in the reading-room of the cafe, situated on the floor level with the street.

Mr Waters states that he went to bed about midnight, all his employees having gone to bed previously. He saw to the fires in the various rooms before going to bed; and states that in his opinion they were perfectly safe. After he was in bed a manservant, named Brodrick, came to him for the key to let a boarder in, got the key, let the boarder in, and returned the key to him. Then he went to sleep, and was awoke by loud cries of "Fire!" This, therefore, is all he can state as to the origin of the fire. He actually knows nothing about it.

SPREAD OF THE FIRE. From the time Mr Hall first saw the flames until they were shooting out of the front windows cannot apparently have been above ten minutes, if indeed it was so long. All this time they were mounting up the building, and this they appear to have done at a great rate - in fact, as they came through the front they were already into the top storey, and along the passages the draught carried them right to the Athenaeum end of the building, and it was very little time before they were seen at the windows there. Nothing then could save the building. All the inside partitions were wood, the stairways and passages were like so many flues, and the whole of the inside was a vast roaring mass of fire in less than half an hour from the fire getting a hold. There was a grand pressure of water — something like 1601b to the square inch — owing to the Silverstream supply being in full flow; but it was dashed against the brick outside walls harmlessly, and the inside got the benefit of the stream only where a window or doorway gave an advantage. Nothing whatever could be saved. We think hardly an inmate escaped with anything more valuable, after his or her life, than the clothes they were enabled hurriedly to clutch.

THE FIRE BRIGADE did not arrive upon the scene until perhaps 20 minutes after the first gleam of fire, or quarter of an hour after Mr Hall gave the alarm. But this is not to be wondered at, for from some unaccountable reason the bell did not ring out the alarm for a very considerable time. The Brigade could know nothing of the fire til they heard the bell. When they did hear it, we think the majority of them showed great alacrity in getting to the station and running some of the lighter gear around. The heavy gear they could not get out without horses, and these were a long time coming, and when they did come the harness was broken and delays occurred from this cause. When the Brigade did reach the fire, we believe they deserve credit for working hard in the way that seemed to them best. Whether that way was best is not for us here to say. They did, however, what they did with energy and spirit, and worked, as they always do, with their whole hearts in the endeavour to stop the flames and save property. The saving of life, however, should have been the primary consideration; it is seen now, at any rate, that it should have been. The Brigade and its officers do not appear to have sufficiently recognised that at the time.

THE FIRE-ESCAPE. The statement made yesterday that the fire-escape was discovered down George street with the wheels off, was an entirely incorrect one. The escape was all ready for action in the station. We have it on good authority that persons who went there seeking it, however, could not get it. It was stated to them that horses were wanted to draw it and when they offered to bring any number of men to take it to the scene, were told that it could not be moved till horse came. Members of our composing staff, who had gone thither after searching in vain where the escape was understood to be kept — at the Masonic Hall — were amongst those who thus pressed to be allowed to take it by hand. In lieu of it, they took ladders across the Octagon. When the horses came the escape was not first taken over to the fire, but some of the other gear. In fact, the escape did not reach the building until half an hour after the bell rang. Now we think there was something wrong here. Certainly some of those early on the scene declare that any time ten minutes after the bell rang the escape would have done no good service; but this does not cover the blame that lies in the fact that it was not there. We think the officers would have been wise to have so ordered a division of labour as to get the escape up before such a lapse as this. Their excuse that horses could not be got is hardly a fair one, seeing that so many willing hands could have been got by a hail from the centre of the Octagon by any of the Brigade men.

ESCAPING FROM THE BUILDING. The first to escape from the premises appear to have been Mr Waters and his wife. He, hearing a cry of "Fire!" turned out, and with his wife made his way out along a passage communicating with the archway on the Stuart street side. On his way out he wakened the man-servant, Brodrick, who also got out in this way. About this time the alarm appears to have become general on the upper floors of the cafe, and judging by the heartrending cries and screams that proceeded from the building, the state of things inside must have been terrible. Those cries could be heard even as faraway as the Daily Times Office. One can imagine what the situation was to a crowd of men, strangers to the place, waking hurriedly out of sleep, finding a raging fire going on below them, being half smothered and stupefied by smoke, if not scorched with heat, and jambed into passages, the outlets from which they did not know. Mr Waters cannot state exactly the number of the occupants of his house that night He judges that about 25 — somewhere between 20 and 30 at any rate — slept in the two upper floors. The kind of thing that happened can best be understood by the recital of few of the incidents attending the escape of those fortunate enough to get out with life.

A man named John Taylor, who had been boarding in the house a week, and who appears to have occupied a front bedroom on the top floor, jumped from his window-sill on to the footpath. He fell heavily, and when picked up by some who had just made their way out, was evidently much injured. He was conveyed to the Octagon Hotel, and admittance not being obtained at once, was placed on the footpath for a time. He was then taken into the hotel, where he was attended to by Drs Murphy and Reimer, but 20 minutes afterwards he died. Taylor was a shoemaker by trade, and had been working for a short time with Mr Loft, in the Arcade, where he has a brother — Charles — now working also. He has a younger brother, a lad working in a bookbinding establishment, and a married sister living at Christchurch but whose husband is meantime in Dunedin. He was identified by his brother Charles at the Hospital yesterday morning.

Taylor, when he fell, was picked up by a Mr J. M. Brown, who, with his brother Andrew, had just left the building. The Browns were in a room on the first floor, directly over Mrs Wilson's shop. They had a quantity of books and pictures which Andrew Brown was engaged in selling in Dunedin. The two appear to have awoke about the same moment, and hurriedly getting into some clothing, but forgetting all about their watches and every thing else that was valuable, got into the passage, where they found Mr Metz rushing out also and giving the alarm. They all got downstairs all right, one carrying his pipe in addition to the clothing he had, and the other taking nothing in his excitement but a blanket and a pair of sofa pillows. Just as they got out, John Taylor had jumped from the top storey, and he was picked up as stated. Mr J. M. Brown is a storekeeper at Invercargill, and proceeded there by yesterday's express. He burned his hand somewhat severely in getting Taylor away from the front of the cafe windows. The books and pictures in the place were of course entirely destroyed, but we believe they were insured in the Victoria office for L200.

Joseph Metz, jeweller and watchmaker, who occupied a room in the building, was among the first to escape, though he returned to endeavour to get some of the other inmates out. He estimates his loss in tools, stock, and clothes at about L70. A bundle containing clothes, which he left at the foot of the stairs, had disappeared when he returned; but we should be loth to join in his belief that it was stolen. He came out with the Browns.

One of the next persons seen to come out of the building was a girl, who jumped from one of the top-storey windows to the pavement. It is stated that a blanket was held for her, but that she missed it. She was injured to some extent, and was taken to the Hospital. She was a servant girl, staying with Mrs Wilson till she got a situation, and we believe had arranged to go to one yesterday. A young man named Beans, who was cook at the cafe, and who slept on the centre floor, was instrumental in effecting a safe way of exit for a number of the cafe boarders. He could not make his way downstairs for the smoke when he was awakened, but climbed out through his window on to the spouting, and along this to a window, where he entered. A clothesline was affixed from this window to an opposite angle of the building, and it worked with a pulley in such a way as to enable clothes to be hung out to dry. Deans got hold of this clothes-line and made it fast in some way inside the room, and called the men from the adjoining rooms and passage to come to him. Some eight or nine men and women thus assembled, and got safely down the rope to the back of the building. One woman, we understand, fell some distance, but her fall was broken by Mr McGill, of McGill and Thomson, and she was hurt but slightly.

Margaret Hill, a girl who was seeking employment through Mrs Wilson's registry office, was sleeping in one of the upper rooms at the back of the building, with two other girls whose names she does not know. She was awakened by the other girls, who were screaming and praying. They went to the window, and one of them jumped right out. Margaret Hill called out to some men below to bring a ladder, and when that was done the two girls descended, Hill being the last. She seems to have behaved with great coolness under the circumstances, for the descent was a long one, and she and her room-mate only escaped in their night-dresses.

One of the most exciting experiences was that of two young men, named Peter Grant (son of Mr Grant, of Gowrie, West Taieri), and Edward Jenkinson (son of Mr J. H.Jenkinson, Port Molyneux), who, being engaged in foundry work in Dunedin, occupied a room belonging to Mr Wilson, and fronting the street on the third storey, being that at the corner next the Athenaeum. Next to their room was one occupied by Fred and Robert Wilson; then came a room occupied by Lily, Louisa, and Sarah Wilson, and the servant Maggie McCartney; and next to this room, directly opposite the stairway, was Mr and Mrs Wilson's bedroom, in which their son, Oliphant, also slept. On the opposite side of the passage was a long room looking to the back, in which four servant girls, waiting for places at Mrs Wilson's registry office, slept. Grant was awoke by cry of "Fire!" and roused Jenkinson. They lit a candle, and found the room full of smoke. Looking out of the front window, they saw the flames coming out of the cafe windows on the ground floor. At the same moment, two men, evidently boarders at the cafe, came to their door, attracted by the light, and crying, "For God's sake, show us an outlet." Grant opened the door, and the room filling with smoke and heat, he and Jenkinson made for the passage. Neither thought of their watches underneath their pillows, nor did Jenkinson remember a purse with about L6 in it on the table. Grant was fortunate enough to pick up a pair of trousers, in which L2 were; he also, as he was going out of the door, picked up another pair of trousers, and his Volunteer carbine and cutlass. Both tried to explain to the two men to follow them, and to show them the stairs. One of the men took hold of Jenkinson and held on till nearly at the top of the stairs, but then let go. As they reached the top of the stair, a tongue of flame was roaring along the passage. How they reached the bottom floor neither knows, but after getting outside and having a breath of fresh air, the subject of what had become of the two men and of the Wilson children was broached. The two agreed to go upstairs again, and although they describe the heat as something fearful, especially on the centre floor, they did get up, Grant leading. Just on the landing Grant found Louisa Wilson, whom he took in his arms. It was impossible to go any farther, and another scramble downstairs succeeded. Both state that when they turned to go back they despaired of reaching the bottom again. However, they did so, both getting burned on the hands and also on the face slightly, with the addition of a good deal of singeing about the hair. On the way down they met three policemen attempting to make their way upstairs, but these were unable to get beyond the first landing, where they sang out to attract the attention of those above. Grant took Louisa Wilson to the Octagon Hotel. In the meantime Lily Wilson had got out of her bedroom window, and had lain down at full length upon the parapet below the window-sill to escape a tongue of flame coming out. Jenkinson saw her, and a blanket having been got, he called out to her to throw herself down. She did this, but striking an archway over the street door, she gave a rebound outside the blanket and fell on the pavement. Jenkinson picked her up and carried her to the Octagon Hotel. She was quite sensible, and complained of her back. While Lily was at the window, someone came out of Fred Wilson's window. He clambered along the parapet till he reached the corner, and when Jenkinson went away with Lily he was hanging to it by the hands. The young men themselves escaped with nothing but coat and trousers, and Grant handed over the extra pair of trousers he brought down to an unfortunate fellow he found downstairs without any, and who asked for them.

The above are a few of the incidents of escape, and from them it may be imagined what scenes the spectators below had to witness while they stood helpless. The mass of people was excited to the utmost degree, and there are many who will remember the night as a night of horror while they live.

THE LIVES LOST. The premises having been pretty completely gutted by daylight, steps were taken to discover what, if any, bodies remained in the building. There was the greatest uncertainty on this point. It was over and over again stated that Mr and Mrs Wilson had been seen walking in the Octagon — a report, however, many were only too sorry to disbelieve, for if alive they must have made some effort to get knowledge of their children. It was about 7 o'clock when it became known that the bodies of Mr and Mrs Wilson had been seen. It is difficult now to ascertain from the firemen who found the bodies, and who were no doubt working under great excitement, in what order they were found. It appears pretty certain that they were found all in their own bedroom. It was about 8 o'clock in the morning when the bodies of Mr and Mrs Wilson and the little four-your-old were recovered, and just about the same time the bodies of their daughter Sarah, and the maidservant, Maggie McCartney, were found. Between the room which the last-named had occupied and the Athenaeum corner of the building the floor had given way and fallen down to the next storey. Right at the bottom of the sloping floor, and underneath the remains of a bedstead, were found two bodies. One is evidently that of Fred Wilson and the other is believed to be that of a man named Swan, of whom the police can gain no particulars, although we have heard he was a bootmaker, and an employee of Messrs Reynolds, Clark, and Co. Probably he was one of the cafe lodgers who had found his way to this end of the building, and had been overpowered by the smoke. Swan was a passenger by the Cape Clear from Glasgow. These bodies — those of the Wilson family, their servant, and the man Swan — were all found in the corner of the building farthest from where the fire broke out. Bobby Wilson, who slept in the same room with his brother Fred, has not yet been found. His body will probably be discovered in the same corner.

On the cafe side of the building, at about 1 p.m., another body was got. This is judged to be that of George Augustus Martin, aged 23, son of Mr G. A. Martin, the well-known musical conductor. Martin will be remembered in consequence of his connection with the Athenaeum arson case, in which he figured as a principal witness for the Crown against Cummock.

Shortly before 3 p.m. a tenth body was recovered. He had evidently been an elderly man, and wore a truss, which may aid in leading to his identification. No one has as yet turned up who knows anything of him. These, then, are the whole of the bodies taken from the ruins up till dusk last night. They are - Robert Wilson, Sarah Ann Wilson, Frederick Wilson, Sarah Wilson, Lawrence Oliphant Wilson, Margaret McCartney, George Augustus Martin, _____ Swan, a man unknown.

The body of Robert Wilson, jun., is known to remain still in the ruins. And besides the above, there also lies at the Hospital the body of John Taylor, who died after jumping from the upper storey, as above stated.

Last night a person called upon the police, stating that up till 11 p.m. he was playing draughts in the cafe with an elderly man, a shepherd, who he believed slept in No. 6, and of whom he had yesterday been able to learn nothing. It is possible this shepherd is the man described as unknown, while again he may have got out in safety.

THE PERSONS INJURED The persons now in the Hospital suffering from injuries received in escaping are, Lily Wilson, who has a wound on the arm, a scalp wound, and superficial burns on both legs.

Louisa Wilson, who suffers only from burnt hands.

Annie McFadyen, who has suffered injuries to her back.

David Thomson, who is bruised on the left hip, and ribs. The latter is a young man who has for the last few days been working for Mr Vezey; butcher, Princes street south. He was previously working for Mr Hellyer, butcher, in Walker street. His account of how he got hurt is that he jumped from a high window somewhere. Probably he was one of those who dropped from the parapet into the right-of-way. The whole of the above are getting on famously, and are wonderfully little injured considering the falls they all, except Louisa, received.

A very painful circumstance in connection with the two girls Wilson is that they know nothing of their parents' fate. They wonder why they do not come to see them, and the younger especially calls plaintively for "mamma," and thinks every soft foot approaching is hers. No one has yet been courageous enough to break the sad news to them, that they alone are the survivors of the family circle. Poor things, they will learn it all too soon.

GENERAL It would be impossible to describe the sensation this event has created in Dunedin. We imagine the city has not been such a sorrowful frame of feeling since the Pride of the Yarra calamity, when the Campbell family met watery graves together, cooped up in the small cabin of a harbour steamer, and within hail of the "promised land" of their adoption. The case of the Wilson family has excited a like commiseration as then existed. In spite of the wretchedly wet weather which prevailed in the city yesterday, a constantly coming and going crowd of people, numbering a couple or three hundred, was gathered about the scene of the fire, and the slightest scrap of information was eagerly listened to and canvassed. The building came in for a large share of disapproval. It was a kind of rabbit-warren on a large scale on the upper floors, built without a brick partition throughout to stay the flames, and several of the occupants of the building had often entertained fears for their safety in the event of a fire breaking out. Mr Wilson, to our own knowledge, had often expressed an opinion that a fire in Ross' Buildings would result in loss of life. He was but too true a prophet.

In the excited state of affairs yesterday we were not able to give much attention to the securing of details of the actual losses sustained by occupants of the premises; but, as we said before, nothing whatever was saved. None of those who escaped saved anything but the clothes they stood up in when they got out, except as in such cases as that of the young Volunteer who carried his carbine and cutlass to safety with him, only to fling them from him in disgust when he became conscious that he had them. None had time to do anything but think of dear life. The insurances, so far as we have been able to get them, are as follow: Union, L1000; Standard, L1100; National, L1450; Norwich Union, L1400; Victoria, L1200; Hanseatic, L400; United, L500; Hamburg and Magdeburg, L700: total, L6800. The distribution is somewhat in the following order: — National, LI300 on building and Ll50 on contents; Union, L1000 on building; Standard, L1000 on building, L100 on Mr Litolf's (music teacher) effects; Norwich Union, L1300 on building, L100 on Mr Drysdale's goods; Victoria, L200 on Mr Brown's goods; Hanseatic, L400 on Mr Waters' stock and furniture; Hamburg and Magdeburg, L700 on Mr Maxwell Bury's (architect) effects. Mr B. Wilson had an insurance of L200 over his stock and effects in the New Zealand office.

The following further particulars appear in Wednesday morning's 'Daily Times': —

TWO MORE BODIES FOUND. During yesterday some half-dozen Corporation workmen were engaged in searching the buildings for human remains. Two more bodies were found, neither of which has been identified. One was got shortly after 9 a.m., in the portion of the premises above Ross' offices, close to where the remains of George A. Martin were recovered the previous day. There was nothing but a small collection of bones picked up here, which could be put into a small bag, and the remains are in a thoroughly unrecognisable state. One or two suppositions have been bruited as to their identity, but in the meantime nothing is certain. At about 4 p.m. another body was discovered. This was found at the cafe end of the second floor, lying partly underneath a fallen ceiling. It thus may have come from the third floor. It is believed to be the remains of a full-grown man, but is perfectly unrecognisable.

The burnt bodies recovered, therefore, to date number 11. Mr Wilson's son Robert is not among them; for it is hardly possible to suppose that his was the body found yesterday morning, as this was got altogether at the other end of the building, and on a different floor to that on which young Wilson slept. Three of the bodies now in the Hospital remain unidentified. The man Swan, found along with Fred Wilson, and regarding whom no particulars could be given yesterday morning, is now, we understand, known to have been a stonemason, who arrived in the Colony about 10 days ago by the ship Nelson (not the Cape Clear) from Glasgow. He had taken up his abode in the premises only two days previous to the fire, and had arranged to go to work at Mr Munro's on Monday morning. His full name was John W. Swan.

The shepherd reported to have been playing draughts in the cafe the night before the fire, and not to have been seen since, has turned up all right. His name was John McConley, of Greenfield Station, and he slept in one of the rooms, but got out safely. He lost three Ll0 notes by the fire.

The tenants of the first floor were as follow: — A. Brown, F. A. Little, M. Bury, ____ Litolf, J. Metz, — Dodds, — Jackson, G. A. Martin, W. Moule, and Joseph Mackay. Of these Brown, Metz, Martin, and possibly Dodds (or Dodson) slept on the premises. Brown and Metz are among the escapees. Mr Bury, the architect, had his property damaged to a less extent than any of the others. — Many of his drawers containing plans were almost uninjured by fire, although, of course, more or less drenched by water. — Mr Joseph Mackay has, we understand, lost a good deal of his almanac plant, such as stereotype plates, a quantity of type, books, &c. Mr Ross is a heavy loser. His furniture and effects were insured for L200, but the plans and papers destroyed are of much more value. Mr E. M. Roach, who carried on Mr Ross' business, is also a heavy loser. He lost the whole of his papers and appliances, but he can scarcely as yet judge the real extent of his loss.

The total insurances upon the building, pure and simple, amount to L4600, divided as follows: — L1300 in the Norwich Union, L1000 in the Standard, L1300 in the National, and L1000 in the Union.

Mr Drysdale, drysalter, was in the Norwich Union for L500, instead of L100 as stated.

There was no foundation whatever for the report which was put about yesterday, that an arrest had been made in connection with a suspicion of incendiarism. We believe there is no suspicion of the kind entertained by the police, and certainly no arrest was contemplated or made. It has been stated that the police had given notice to Mr Waters that his concert room in connection with the cafe would have to be closed. A notice somewhat to this effect had been given, but Mr Waters had sent a reply to the authorities which in all probability would have opened the thing up afresh. From what we can learn, Mr Waters tried fairly enough to keep the affair respectable and orderly, only occasionally — and especially on Saturday nights — "rowdies" would get in. The concert was a paying concern, and was a valuable adjunct to his business; and it was to Mr Waters' interest to keep it orderly, and so secure a continuance of the license to it. With this view he had offered to meet the authorities in every possible way, being willing even to pay a fee to secure the nightly attendance and supervision of a constable, as at the theatres. These are facts that will probably come out at the inquiry, but it is only justice to Mr Waters to let them become known as soon as possible.

Little of any value in the shape of property has been recovered from the ruins. L6 in sovereigns was found, and is in possession of the police, and some studs have also been got. But the police know nothing regarding the finding of watches, of which reports were current yesterday. The building inside was by no means of so inflammable a nature as we were previously led to suppose. The partitions were not of wood at all; the three main partitions from front to back were of solid brick, and all the intervening partitions and the ceilings were of lath and plaster. The two staircases and the passages running through the whole length of the building were probably enough designed with the view of affording easy egress in case of fire; but the long passages, with open entrances at either end, seem to have caused a draught that no doubt greatly accelerated the progress of the fire. We have been requested to contradict the statement that has been made to the effect that an insurance company declined a further risk of L1000 on the building recently. We are assured by the agents of Mr Ross — Messrs Reid and Duncans — that the insurances stand exactly as they were when Mr Ross left for Home, and that no attempt has been made to increase them.

With regard to the patients from the fire at the Hospital, the attendants do not now speak quite so favourably, except as regards Louisa Wilson. She will leave her bed today. Lily Wilson complains more than previously of pain, and is more restless, and David Thomson also has intervals of pretty severe pain. The girl McFadyen does not show any marked improvement. None of the three cases, however, is regarded as dangerous, and there is every hope that the sufferers will recover. The Wilsons have not yet been made aware of the fate of their parents and brothers and sisters.

Operations in the way of searching amongst the ruins were entirely suspended on Wednesday. The City Surveyor has given it as his opinion that nothing further can be done, and that it is next to impossible that any more bodies can remain in the building. So far, three of the bodies in the Hospital are unidentified — indeed they are unidentifiable. One can scarcely be called a body; it comprises merely a small collection of bones, which are believed to be those of a young person. It is suggested, therefore, these remains may be those of Mr Wilson's son Robert. As they were found in the opposite end of the building to that occupied by the Wilsons, and on a different floor, this belief is tenable only on the supposition that the lad had wandered all this distance in an endeavour to get out, and this, as he would be going the whole way right in the face of the advancing flames, seems the reverse of probable. The only other conclusion, however, would be that he is still in the building, and against that we have the above-stated opinion of the City Surveyor.

The bailiff Dodson has turned up all safe. We, elsewhere, state the supposition that this Dodson and "Dodds," marked as one of the tenants of a room on the agents' plan, were identical, but Messrs Reid and Duncans state that Dodds was the correct name of their tenant. He was a young man, and occupied a room on the second floor. Whether he was in the building on the night of the fire is a mystery; indeed, no one appears to know or have heard anything about him.

We heard last night also that a girl named Kate Moore, who had stated that she had put herself down on Mrs Wilson's registry books as seeking a situation, has not been seen since the fire. The last time she was seen was on Saturday morning, and her relatives and acquaintances are concerned about her safety, thinking she might have been sleeping in the building. She left her carpetbag at the rooms of the Dunedin Young Women's Christian Association, and has not since called for it.

The sufferers at the Hospital are reported to be much in the same condition as on Tuesday, the young man Thomson complains greatly of pain at intervals. Early on Wednesday morning Sir George Grey telegraphed as follows to the surviving member of the Wilson family: — "Christchurch, September 10th, Misses Wilson, Hospital, North Dunedin. I feel so much for the misfortune which has fallen on your family that I cannot refrain from intruding to express my deep sympathy in your sorrows and sufferings. G. Grey." The telegram arrived by Mrs Walter, who has been unremitting in her attentions to the Misses Wilson, and was replied to as follows by the Mayor: — "Dunedin, September 10th. Sir George Grey, Christchurch. The Misses Wilson are not yet acquainted with their loss. Accept thanks on their behalf for your sympathy. Progressing favourably." H J Walker -Otago Daily Times, 12/9/1879.

THE LATE FATAL FIRE IN DUNEDIN.

[from our special travelling correspondent.] Dunedin, Sept. 14. Finding that the time could be spared, I decided last Friday night to run down to Dunedin to make personal inquiries into the recent disastrously fatal fire in the Octagon, the news of the occurrence of which, flashed by telegraph to the remotest parts of New Zealand and Australia, sent a thrill of mingled horror and indignation throughout the Colonies — horror, at the shocking fate which befell twelve human beings, and indignation at the carelessness, blundering, and incompetency if, alas! not worse, which apparently were at the bottom of the catastrophe. Remembering how well Dunedin is supplied with daily journals, some of them ably conducted, it might have seemed, unnecessary that a special reporter should have come from such a distance as Christchurch; but — even at the risk of offending some of my confreres of the quill — I must say there existed in my mind an uneasy feeling that the whole story was not being told. I knew something of the character of the building, and it struck me that (probably on the doctrine de mortis nil nisi bonum, frequently carried to such an absurd extent) the Dunedin Press kept back certain disgraceful facts. Again, bearing in mind the petty jealousy that a section of this community displays towards centres of population more favourably situated, it seemed not unlikely that, ashamed of the absurd building regulations in force, and of the inefficiency of the Fire Brigade, a wisely discreet silence on these points was being maintained. Rightly or wrongly, these considerations induced me personally to institute inquiries on behalf of the Lyttelton Times, and within a very few hours of my arrival here I had proof that I had not been very far wrong. Of this, however, the reader will shortly be able to judge for himself.

In these days your "special” must decide promptly and act rapidly; consequently within 18 hours of resolving to come I was taking mine ease in Wain’s familiar hostelry, assiduously attented to by the ever-green Fred. After dinner I strolled through crowded and brilliantly-lighted Prince’s street into the expanse of the Octagon. This, too, was well lighted, with the exception of one dark, dismal corner away to the right where — it required no guide to tell it — stood the blackened ruins of the ill-fated Cafe Chantant. How the name with its abominable associations grates upon the ear! Approaching it, I found the building surrounded by a barricade, and carefully guarded by a policeman; while from an adjacent dark entry a watchful detective followed my movements. That there is ground for suspicion that an atrocious crime has been committed there will be evidence to show before this paper is concluded. Here and there about the barricade were groups of boys, even their irrepressible mirth silenced in contemplation of that weird hecatomb. Occasionally a group of mechanics, or an artisan and his wife, returning from their Saturday night’s shopping, would stop for a moment, glance sadly, possibly tearfully at the dreary spectacle, and pass silently on. Once I was startled by a woman's deep sob, but I did not see the sorrower — the voice came from out of the darkness. The next minute I am in the a thronged streets again, and, having arrangements to meet Inspector Mallard at 11 p.m., turn into the Theatre if only by way of relief to the feelings. The Linsards are playing the comic opera of "Le Petit Duo," and the audience is convulsed with laughter. A few hours previously, the city had been in sackcloth and ashes. Fifteen thousand people had mournfully witnessed the procession following to their last resting place the poor, charred mortal remains of the victims of the fire. Now we are making merry, and the world goes on as usual. Well that it is so!

I found Inspector Mallard, a prompt, soldiery officer, and a courteous gentleman, one with whom there was no necessity to beat about the bush. I handed him my card, and told him my business. "Well," he said, “tell me exactly what you want me to do.” My reply was, “I want you to place at my disposal an intelligent officer, who is familiar with the circumstances of the fire, to go over the place with me. I also want you to lay me on the track of the most intelligent and trustworthy of the survivors, and I will also feel indebted to you for any information you may personally volunteer.” Inspector Mallard’s reply was characteristic. He said; “Well now, if give you the sort of officer you want, the chances are that he will tell you too little and too much. I would have to instruct him beforehand. Therefore, I will go myself with you to-morrow forenoon at 11 o’clock. As to the other matter, that is more difficult, but I will think it over."

Then followed a general conversation, in the course of which Mr Mallard gave me some information respecting Waters, the proprietor or manager of the Cafe Chantant, and spoke strongly against the use of the Mansard roof, attributing the rapid spread of the fire in this instance to it. All this, however, will have to be referred to further on. It will assist the reader to follow my narrative, if he will bear in mind that up to this stage it has been written on Sunday morning, and that I now lay down the pen to keep my appointment with Mr Mallard.

Sunday Afternoon. Accompanied by Mr Mallard, about two hours have been spent in an examination of the building, and in listening to details of the fire. The first thing to be done, in order that the following account maybe clearly understood, is to describe the position of the block, and as I am writing mainly for readers who are familiar with the topography of Christchurch, perhaps the better plan is to take a local illustration. Assuming Colombo street to be Prince’s street, and Cathedral square the Octagon, then Ross’s Buildings would occupy the position between the offices of Messrs J. B. Dale and Co. and Worcester street (Stuart street in Dunedin). Looking at it from the Cathedral, it would have the appearance of a rather imposing two-storied stuccoed brick building, with a large covered archway on the extreme left, and three large shops between the archway and the extreme right. Above this another story, presenting a row of nine large windows to the street, the whole surmounted by what is called a Mansard roof, of which more anon. Going to the rear looking though from the corner of Manchester and Worcester streets across a piece of low-lying ground, the back of the building is three-storeyed, the ground sloping so rapidly from the Octagon street level that there is room behind for extensive cellarage, the walls of which are constructed of bluestone. The Mansard roof is nothing more nor less than a superstructure of wood erected on the flat roof of the brick building, with sloping sides of galvanised iron divided internally by the flimsiest partitions into sleeping apartments. Place such a building as I have described on the site mentioned, with a narrow right-of-way separating it from Dale and Co.’s offices, and the Christchurch reader will have an excellent idea of Ross’s “rabbitwarren" in the Octagon, Dunedin. I have been thus particular in describing it, because Christchurch and every large town in the Colony is interested in the causes that led to the fearfully rapid spread of the recent fire.

We now come to the interior arrangements. The shop on the left hand was occupied by Waters, and used as a Cafe Chantant. His patrons went from the street straight into the cafe, at the extreme end of which was an arched alcove, used during the day as a reading-room, at night transformed into a stage. Behind this a narrow angular staircase led up to the bedrooms and down to the cellarage, in which latter were the kitchen and Waters’ sleeping apartments. To this alcove there was also a side entrance in the Stuart street gable-end, to be reached by proceeding down the aforementioned archway. The centre shop was occupied by the deceased Mrs Wilson as a drapery warehouse and servants’ registry office, and between it an the next shop (unoccupied), on the extreme right, was a doorway, open day and night, leading to a second staircase. It will be understood, then, that there were only two ways of reaching the upper storey — one through the Cafe Chantant, and the other through the middle entrance. For example, Mrs Wilson could not go upstairs from her shop, but had to go out into the street, and through the last-mentioned entrance. This gives us three entrances into the ground-floor, one through the main entrance of the cafe, one through the side entrance of the cafe and one, kept continually open, situated nearly in the centre of the building. As to the interior partitions they were shamefully flimsy; people here, amongst whom deep indignation is expressed, freely saying that no architect would have dared to put up a similar building for a customer. All this description, although perhaps a little tedious, is necessary not only for the elucidation of what I have yet to write, but may possibly prove of deeper interest when, after the inquest now being held, the whole history of the fire comes to be told.

Having done with the building, we now come to the occupants, and I need make no apology to Mr Waters for giving him pride of place. Some short time ago this gentleman came to Dunedin, and conceived that it would be conducive to the morality of the rising generation — possibly, too, to his own profit — that he should open a singing saloon, to which he gave the more euphonious designation of the Cafe Chantant. The aforesaid shop on the extreme left of Ross’ buildings was made what is generally called “the body of the hall,” the arched alcove being at night transformed into a stage. Rows of forms and a piano completed the furnishing of this delightful home of the Muses. Members were not ballotted for; the disbursement of a sixpence entitled the patron to a cup of coffee, a bottle of “pop,” or a cigar, and to participation in as much blackguardism as it is in the power of Colonial larrikins to display. With the exception of the versatile Mr Waters, and a late member of the Georgia Minstrel Troupe, there was no professional talent, the singing, dancing, &c., &c., being provided by amateurs from the audience. Upon only one occasion were “ladies” admitted [on this occasion 9d, I believe, admitted a gentleman and “friend,”] Mr Waters wisely succumbing to a hint from the police. The proprietor had the audacity to petition the Corporation to exempt him from the usual music-hall licence, on the plea that the establishment of this den of iniquity “on strictly temperance principles” was a public benefit. This the police opposed, on the ground that Waters was making money rapidly, and could well afford to pay. In the meantime they kept a watch upon the place, and frequently warned Waters as to the inevitable consequences of allowing rowdy conduct. At last, on the night of Saturday, Sept. 6, Inspector Mallard — acting, I presume, on information received — visited the Cafe, and what he witnessed induced him to tell Waters that the police would take immediate steps to have it shut up. The fire took place on the morning of Monday, Sept. 8, and the police — perhaps fortunately for Waters — were saved further trouble in this direction. Of the other inmates of the building I will only speak of one family by name — the Wilsons. Their sleeping apartments were in the extreme right-hand of the Mansard roof, the most distant point from the cafe. The family consisted of Robert Wilson, sen., aged 59; Sarah Wilson his wife), aged 40; Frederick Wilson, aged 19; Sarah Wilson, aged 8; Lawrence Oliphant Wilson, aged 4; Robert Wilson, jnr., aged 10; Lily Wilson, aged 16; and Louisa Wilson, aged 13. Of these all except Lily and Louisa perished in the flames. Lodging with the Wilsons were three or four girls, sempstresses or domestic servants, waiting for situations, and I distinguish them thus particularly from other inmates of the building because I am anxious to except them from certain comments about to be made. They were under the personal supervision of Mrs Wilson, and were guarded from communication with the class about to be referred to. Some of the rooms on the second storey were let as offices, unoccupied during the night; others were let as bedrooms to young men in various grades of life, who took their meals elsewhere. Now, if the reader will bear in mind that the street entrance to this storey was open day and night, that the social evil cannot he said to be stamped out in Dunedin, and, moreover, that the building was in close proximity to one of the most notorious rows of cottages in the city, he will not require to draw deeply on his imagination as to what may have happened. But, in this case, it is unnecessary to draw upon imagination at all, as I have it on the authority of a frequent eye-witness that the scenes sometimes “beggared description“ — to which summing up it is not required of me that I should add a single word. The reader now has before him the building and the inmates — the cafe, with its ruffianly patrons, the shops and dwelling-rooms of the respected and hard-working Wilson family; and the bachelors’ quarters, the scene of nightly orgies.

We now come to the fire, and here I may at once say that it is not my intention to trench upon the exhaustive details already published in the columns of the Lyttleton Times. I shall confine myself to placing the reader in a position to form an opinion — perhaps I should say to guess — as to how the fire occurred, and to explain, for the benefit, I trust, of the community at large, why the flames spread with such fearful rapidity. The door in the gable-end of the building, approached through the archway, and leading into the Cafe Chantant, was usually left during the night unlocked. On Sunday night it appears, however, to have been fastened in some way, for a man (unknown so far as police are concerned) was seen to go to it and, failing to open it, knocked for, and obtained admission. This probably is the last person, who, previous to the breaking out of the fire, entered the building by that door, although it is quite impossible to say how many may have gone in and come out by the general entrance. About 2 a.m., on Monday a neighbour observed fire in the cafe and there is abundant evidence to prove that it broke out close to that portion occupied at night by the stage and within a few feet of the narrow staircase leading from the rear of the cafe to the upper storeys and down to Mr Waters's bedroom. Now, mark the effect — the moment the fire made headway, the staircase became a flue with terrible up-draught; the flames rushed up this, along the passage in the Mansard roof, and down the staircase at the other end of the building. Those who know the effects in the up and down-draught ventilation shafts of mines will immediately comprehend the position. The flames, rushing up the staircase at one end of the doomed block, along the tindery passage, and down the only other staircase, instantly cut off all means of escape, and terrible loss of life ensued. What I am particularly desirous of pointing out is that these Mansard roofs are a snare and a delusion. The great fire in Boston in 1872 conclusively proved that they were a failure as regarded protection from external fire, i.e., sparks falling upon them, and the Octagon fire proves with equal conclusiveness that, as regards internal fires, they are cruel traps for those who have the misfortune to sleep under them The one in question was erected just previous to the passing of a by law prohibiting them within what is known in Dunedin as the “inner circle,” but it is probable that the result of the late conflagration will cause the Corporation to extend the prohibition to all parts of the municipality.

Shortly after finishing the inspection of the Buildings, I was introduced to His Worship the Mayor of Dunedin, Mr H. J. Walter, with whom was a very old friend, Mr Abraham Barrett, Rector of the Middle District School. Mr and Mrs Walter have been indefatigable in looking after the wants of the injured survivors of the catastrophe, Mrs Walter having undertaken the terrible task of breaking to the two Wilson children the intelligence of the fate of their father, mother, two sisters and three brothers. It was suggested that I should call upon these two poor little waifs in the hospital, and I did so. It is surely needless to say that in my capacity as a journalist I should never have dreamed of intruding upon their sorrow; and it was only when it was represented to me that it would please them to see a friendly face from a distance that I consented to enter the ward. The eldest, Lily, 16 years of age, was sitting up in her cot; the youngest, Louisa, 13 years of age, dressed, poor child, in deep mourning, sat beside her. I spoke to them for a few minutes, but I frankly admit I would rather again — as I have often done before — “face the music” of the batteries, than look into the sad, wistful eyes of the children who have gone through that most fearful baptism of fire, and, deprived of all that makes young life dear, have the world before them. Let us hope it will deal tenderly with them. My friend, Mr Barrett, informed me that they were pupils of his. He spoke of the elder girl as being remarkably lady-like in demeanour, and of the younger as displaying rare cleverness. For my own part, I can say that they are pretty and intelligent-looking, and quite apart from the special interest now attaching to them, would attract attention. Strange to say, a fatality seems to have followed the class in school to which they belonged, one of their little companions having last week fallen and broken one of her legs. The three children are now all together in one ward of the hospital. I did not succeed in discovering “the intelligent survivor.” The time at my disposal has necessarily been very limited, and it could not be wasted in looking for the proverbial needle in a bundle of hay. Mr Waters, as the reader will quite understand, I did not consider it desirable to call upon. The Wilson children were out of the question, and amongst the others I could not learn of one whose statement I would have gone to the trouble to take.

These are the results of my visit to Dunedin for the purpose of enquiring into the tragedy which has cast a gloom over the whole Colony. Of two things I am convinced — firstly, that the matter requires the most searching, laborious, and unremitting investigation, in order that, if possible, the origin of the fire may be ascertained; secondly, that whatever may have been the origin, accidental or otherwise, the rapidity with which the building was destroyed and the shocking loss of life entailed, demand the most serious attention of architects, builders, and Corporations.

It will be understood that as the inquest is still proceeding, and the matter is in other respects sub judice, there are several particulars within my knowledge in connection with the fire and subsequent police investigation which, in the interests of justice, it is undesirable should at this juncture be made public.

[It will be seen from a telegram in this morning’s issue that Waters has been arrested on a charge of arson.]

I append the following excerpt from the eloquent funeral sermon preached on Sunday by the Rev Dr Roseby, of Dunedin: — The peaceful hours rolled silently by, the City lay deep in slumber, when the startling clang of fire, alarm, mingled — even at the distance of my own residence — with the shrieks of human beings in the agony perhaps of death, broke on our ears. Those who reached the scene during the occurrence of the heart-rending events which happened on the first alarm saw what can never be forgotten while reason holds its sway. There are some things that are burned into the memory as with a brand of iron. The frantic efforts to escape of the poor creatures, who could be seen through the smoke clinging to the window sills and parapets; the desperate leap of some, fatal, alas, in the case of one; the escape of others by the happy discovery and ingenious use of a piece of rope; and the tardy escape of others by the ladders arriving all too late except to save a scanty remnant of three — what memory can cease to retain this fearful chapter of horrors, or what tongue can describe them. Still more the horrors of the scene within cannot be imagined. What it must have been to be aroused at the dead of night from the deepest slumber to find oneself hemmed in on every side by fire, and every avenue of escape destroyed by the fierce element; to be unable to do anything to save those dear to one as life itself; to be shut in by the cruel flames so as not even to be able to die in the moment of brief endeavour, but to die in agony and brief convulsive struggle, a death by suffocation. Willingly I draw a veil over a scene which paralyses the imagination with horror. How tantalising also to have the means of escape so near and yet so far; for hundreds of people to be looking on and yet unable to render the least assistance; for a fire-escape, by the swift and deadly power of the flames even more than by its own tardy arrival, to be found of no service in the one and only instance wherein its aid had been required. How tantalising indeed such circumstances in the sad event. Then came the dreary search — the turning over of many tons of debris; the discovery of memorials full of touching sadness, of a busy brain now still, of a warm heart now cold in death; the rescue not of the living but of the dead. Yesterday came the last scene of all. The testimony of universal sympathy in the long procession and crowded streets; the dismal pageantry of woe; the minute bell, its too familiar tone apt to startle by its suggestions of fire rather than to impress by suggestions of death; the yawning pit to which were committed the mortal remains of father, mother, daughter, and sons; the words of prayer; the tears of honest friendship, the last farewell of fellowship. -Lyttelton Times, 16/9/1879.

The Late Fatal Fire in Dunedin.

— The inquest on the fire has been adjourned until to-day. W. Waters, proprietor of the Cafe Chantant, where the fire is supposed to have originated, has been arrested on a charge of arson. -Temuka Leader, 17/9/1879.

THE 'LYTTELTON TIMES' ON THE OCTAGON FIRE.

The Octagon fire has been "done" by a specially-travelling correspondent (we wonder he did not adopt the title of commissioner very much in favor with his journal) of the 'Lyttelton Times' in a way that is not creditable to first-class journalism. The efforts of this "special," which have produced only a couple of columns of type, and they include a substantial extract from the columns of one of our local contemporaries, are introduced by an apology for them that covers a charge, wholly unsupported, against the Dunedin Press: — "Remembering how well Dunedin is supplied with daily journals, some of them ably conducted, it might have seemed unnecessary that a special reporter should have come from such a distance as Christchurch; but — even at the risk of offending some of my confreres of the quill — I must say there existed in my mind an uneasy feeling that the whole story was not being told. I knew something of the character of the building, and it struck me that (probably on the doctrine de mortis nil nisi bonum, frequently carried to such an absurd extent) the Dunedin Press kept back certain disgraceful facts, bearing in mind the petty jealousy that a section of this community displays towards centres of population more favorably situated, it seemed not unlikely that, ashamed of the absurd building regulations in force, and of the inefficiency of the Fire Brigade, a wisely discreet silence on these points was being maintained. Rightly or wrongly, these considerations induced me personally to institute inquiries on behalf of the 'Lyttelton Times.' and within a very few hours of my arrival here I had proof that I had not been very far wrong. Of this, however, the reader will shortly be able to judge for himself." We have read and re-read the "special's" report, but have failed to discover in it the slightest attempt to prove his assertion that the Dunedin Press kept back disgraceful facts. It is certainly said towards the end that "there are several particulars within my knowledge in connection with the fire and subsequent police investigation which, in the interests of justice, it is undesirable should at this juncture be made public." This report was presumably written on Monday night. Would it surprise Mr "Special" to learn that the Evening Star knew as early as Friday last the substance of the disclosures made at the inquest on Monday last, but, conscious of the unfairness to the party implicated of publishing them in anticipation, declined to do so? If that is keeping back disgraceful facts in the sense implied, then we plead guilty. Mention ought also to be made that the local telegraph agents were also aware of the circumstances. We have nothing to say about the prominence given to the sayings and doings of "Mr Special" — we know it is in some quarters regarded as a proper feature of penny-a-lining — or to the taste shown in chronicling the semi-private opinions of people with whom he was brought into contact; but we do protest against the insinuation made against the local papers in the opening paragraph of this report and against the misstatements. Whether the Cafe Chantant had "ruffianly" patrons the police are best able to say; but we are inclined to think that the statement that "the bachelors' quarters" in Ross's buildings were "the scene of nightly orgies" will be resented as a gross libel. Of our knowledge, the aforesaid bachelors' quarters were occupied by people whose respectability it is beyond the power of the 'Lyttelton Times' special to question. -Evening Star, 17/9/1879.

William Waters, the proprietor of the Octagon "Cafe Chantant," was brought up at the Dunedin Police Court on Tuesday evening, charged with having "unlawfully maliciously and feloniously" set fire to Ross's buildings. No evidence was taken, and he was, on the application of Inspector Mallard, remanded to Monday next. The enquiry into the origin of the fire is still going on, and a writ of habeas corpus has been obtained to enable Waters to be present during the proceedings. The enquiry was again adjourned to 7 o'clock last night to give the jury a rest; the Coroner was then to sum up. -Bruce Herald, 19/9/1879.

THE RECENT FATAL FIRE. (abridged)

In our our last summary for Europe we gave a long account of the fatal fire that occurred in the Octagon on the 8th of September, by which the lives of 12 persons were sacrificed. The inquiry into the origin of the fire was commenced on the 11th of September, before Dr Hocken, city coroner, and was not concluded until the 18th. On the 16th during the progress of the inquiry, William Waters, the proprietor of the Octagon cafe chantant, was arrested by the police, charged with wilfully setting fire to a building in the Octagon on the 8th September, Robert Wilson being at the same time an inmate of the building. Waters was present in custody during the latter part of the inquest, Mr J. E. Denniston watching the proceedings on his behalf. The verdict of the Coroner's Jury was as follows: —

"The fire which occurred at Ross' Buildings on the morning of the 8th inst. was the wilful act of William Waters."

The inquest on the bodies of the victims of the fire, which had been commenced on September 8th and adjourned, was then resumed, the evidence being the same as that given in the inquiry into the origin of the fire. After about five minutes' deliberation, the Jury returned the following verdict: — "The fire at Ross' Buildings, the Octagon, was the wilful act of William Waters." This, of course, was tantamount to a verdict of wilful murder against the prisoner Waters, who was then formally committed to take his trial at the Supreme Court on the charges of murder and arson. The trial will commence on Monday next. After the committal of the prisoner by the Coroner, it was considered necessary to hold a magisterial investigation, a full report of which will be found below.

THE PUBLIC FUNERAL. The wide and general public sympathy created by the calamity was well evidenced on September 13th, when the funeral of the six members of the Wilson family, of John W. Swan, and of two others (unknown), took place. Three o'clock was the hour fixed for the start from the Hospital gate in Cumberland street, and at this time very large crowd of people had assembled in that vicinity. Four hearses were provided, and the following bodies were placed in them for burial — Robert Wilson, 59 years; Sarah Wilson, 39 years; Frederick Wilson, l8 years; Robert Wilson, 10 years; Sarah Wilson, 9 years; Lawrence Oliphant Wilson, 4 years; John W. Swan. Two bodies unknown. Upon the coffins containing the two latter the inscription "Unknown" was placed. When the hearses began to move a procession was formed somewhat in the following order: — Members of Naval Brigade and Cadets (Frederick Wilson having been a member of the company), male and female members of the British Hearts of Oak Lodge of Good Templars (of which Lodge Frederick Wilson held the post of chaplain), and a number of Middle District School children, schoolmates of the younger children, —these in front of the hearses. Directly following the hearses came his Worship the Mayor (Mr H. J. Walter), Mr. John Pattison (Octagon Hotel) — both of whom were intimate personal friends of Mr Wilson, — and Mr George Fenwick (manager of the Otago Daily Times and Witness), and the general public, including a large number of the staff of the Daily Times and Witness office, amongst whom Mr Wilson had so long held a place. Many of the principle citizens of Dunedin helped to swell the procession, which continually received accessions along the line of George and Princes streets. All the shops were closed, and the fire-bell gave the funeral toll as the city was passed through. Immense numbers of people thronged the streets to witness the last sad scene in connection with the deplorable accident. At a moderate estimate, we should judge not less than 10,000 people turned out on the occasion. Quite 2000 people accompanied the cortege to the Southern Cemetery. The bodies were all placed in the Church of England portions of the cemetery grounds — a child of the Wilsons' having been interred there about four years ago — and the Rev Archdeacon Edwards officiated at the grave. The Rev. Dr Roseby also read a portion of the Good Templar ritual for the burial of the dead.

On Sunday, September 14th, the funerals of John Taylor and Margaret McCartney, two victims of the fire, took place. John Taylor was the unfortunate fellow who jumped from the front of the building, and was killed; and Margaret McCartney was domestic in Mr Wilson's family. Taylor was buried in the Northern Cemetery, and his funeral was largely attended, amongst those in following being a number of the members of the Bootmakers' Society, the deceased a member of that trade. The Rev. Dr Stuart performed the burial service. Margaret McCartney was interred in the Roman Catholic portion of the Southern Cemetery. A large number of the public joined in the funeral procession, and probably 1000 people were assembled at the cemetery when the burial took place. The Rev. Father O'Leary officiated at the grave.

RELIEF OF THE SUFFERERS. The most widespread sympathy has been expressed for the sufferers by the dreadful calamity, and offers of help soon came forward. The two Misses Wilson, the only two survivors of a family of eight, had been in the Hospital for more than a week before the sad intelligence of the death of their parents and brothers and sister was communicated to them. Over a fortnight ago they were able to leave the Hospital, and since that time they have been well cared for by their friends. A few evenings ago a service of song, entitled "Eva," was given by a number of amateurs for the purpose of raising a fund to assist them, and the receipts amounted to over £120. The other sufferers by the fire, many of whom lost everything they possessed in the world, have not been forgotten. Messrs Fenwick, Kempthorne, and Fish, who have undertaken the duty of organising the collection of subscriptions, met on the 6th instant, when it was decided to send subscription lists to all the principal merchants and shopkeepers in the city, with a request that they would use their influence in getting the cards filled up and returned and returned as early as possible to Mr Fenwick, the hon. treasurer. It was also decided to station men with boxes for receipt of casual subscriptions — two at the Octagon, and one at Brown-Ewing's, corner Princes and Manse streets. It is thought by this means an opportunity will be afforded to all classes to subscribe their mite in passing, an inscriptions of the smallest amount will be thankfully received. In the meantime the Committee will ascertain the wants and necessities of the various persons who suffered by the late calamity. We have not the slightest doubt but that this appeal to the public will be responded to in such a manner as is usual with the citizens of Dunedin. -Otago Daily Times, 10/10/1879.

Southern Cemetery, Dunedin.

THE WILSON FUND.

The following is a copy of a letter sent to his Worship the Mayor yesterday: —

"Middle School," Dunedin, 9th October, 1879. "H. J. Walter, Esq. Dear Sir, — Owing to the generous sympathy of the public, and the gratuitous assistance of the local Press and many warm-hearted friends, we have much pleasure, on behalf of the pupils and teachers of the Middle School, in handing over to you a cheque for the sum of L136, being the proceeds of the popular entertainment held at the Garrison Hall on Thursday evening, the 2nd inst., in aid of the Misses Wilson, who were saved from the Octagon fire.

"We beg to request your acceptance of the said sum of L136 in trust for the joint benefit of Miss Lila Wilson and her sister, Louisa Wilson, who are now in the kind care of yourself and Mrs Walter. —We remain, &c, Abraham Barrett, Head Master. John H. Chapman, First Assistant Master." -Otago Daily Times, 11/10/1879.

SPECIAL TELEGRAMS.

(from our own correspondents.) DUNEDIN. October 15. The charge of murder against William Waters was brought to a close shortly after midnight, and resulted in a verdict acquitting the accused. At the close of the case for the prosecution, the foreman of the jury asked the judge if the jury could give a verdict at once without waiting to hear the defence or the judge's summing. This his Honor refused to allow, and the case for the defence was then gone into. After his Honor had summed up, the jury brought in a verdict of Not Guilty on the charge of murder. -Oamaru Mail, 15/10/1879.

An assault case, in which the parties concerned have recently achieved a notoriety as witnesses in the Waters case, was heard at the Police Court yesterday, before Messrs Logan and Eliott, J.Ps. The complainant was Joseph Triggey, who at the time of the fire acted as pianist at the Octagon Cafe Chantant; while the defendant was John Deans, who acted as cook at the same establishment. The difficulty between them arose on the night of Waters' discharge after the Supreme Court trial, and the cause of it appeared to have been mutual recriminations about charges of sentiment towards the accused, as he happened to be in trouble or in prosperity. The trial over, it appeared that a party of friends, Triggey and Deans being amongst them, accompanied Mr Waters to his home, where the row begin. Deans accused Triggey that whereas when Waters was in trouble he had said it served him right, when he got out of it he was not only the first to shake him by the hand, but followed him home like a dog; while Triggey, in a more or less direct way, returned the compliment. It also appeared that the term "crawler" was exchanged, blows ensued, and Mr Waters had to turn either one or both of them out. Triggey had evidently come off with something else than flying colours in the encounter, for he appeared in Court with a black eye; but even this fact did not appear to touch the feelings of the Bench, for his complaint was dismissed. -Otago Daily Times, 18/10/1879.

Interprovincial

Dunedin, Oct. 21. At the Fire Brigades' Supper last evening, Mr G. W. Elliott, foreman of the jury on the trial against William Waters, stated that everyone had been censured for the Octagon fire, except the proper person, and that was the man who set fire to the building. The jury could not convict a man on the evidence given at the trial for an offence for which he would have to go to the gallows, and he thought that the public generally would share that opinion. -Timaru Herald, 22/10/1879.

Interprovincial

William Waters, alias Woodlock, is again a prisoner in Her Majesty's gaol. He was arrested last evening in consequence of the attachment issued by Mr Justice Williams, on a motion by Mr Charles Woodlock for a writ of habeas as to the production of his child. The latter is supposed to be with Mrs Waters, who has made herself "scarce," and has so far succeeded in preventing her whereabouts being discovered. -Timaru Herald, 23/10/1879.

October 17. In the Supreme Court to-day, Charles Woodlock, through Mr. Edward Cook, moved for a writ of habeas corpus for the production of his infant son, now in the custody of Woodlock’s brother-in-law (William Waters, lately tried for murder) and Woodlock’s wife (alleged to be cohabiting with William Waters). The matter was adjourned till to-morrow. -NZ Mail, 25/10/1879.

News of the Day

We understand (says the Dunedin “Herald”) that William Waters, of Octagon fire celebrity, has received his insurance money, and has gone away, leaving a number of inquiring friends. -South Canterbury Times, 6/1/1880.

It will be remembered that one of the victims of the Octagon fire was a man named Swan, who had a wife and family in Scotland. His Worship the Mayor on Wednesday received the following letter from the Provost of Leith, dated January 7: — "I duly received your letter of November 6 last, with its enclosure, and arranged that the British Linen Company should pay over to Mrs Swan, 19 Ferriers street, in small sums, as she might require them, the amount transmitted (L65 l0s). She is deeply grateful for this unlooked-for assistance, and desires me to convey to you and to the subscribers her heartfelt thanks for the kind consideration shown to her in her forlorn condition. — I am, &c, John Henderson." -Otago Witness, 20/3/1880.

News of the Week

It will be remembered that one of the victims of the Octagon fire was a man named Swan, who had a wife and family in Scotland. His Worship the Mayor on Wednesday received the following letter from the Provost of Leith, dated January 7: — "I duly received your letter of November 6 last, with its enclosure, and arranged that the British Linen Company should pay over to Mrs Swan, 19 Ferriers street, in small sums, as she might require them, the amount transmitted (L65 l0s). She is deeply grateful for this unlooked-for assistance, and desires me to convey to you and to the subscribers her heartfelt thanks for the kind consideration shown to her in her forlorn condition. — I am, &c, John Henderson." -Otago Witness, 20/3/1880.

News of the Week

A tombstone, which is the result of a number of subscriptions, of which his Worship the Mayor (Mr H. J. Walter) and Mr George Fenwick (managing director of the Otago Daily Times and Witness Company) acted as custodians, has lately been erected over the grave of the Wilson family, victims of the Octagon fire. It consists of a white marble slab facing upwards, on a stone foundation, and is situated at the north end of the English portion of the Southern Cemetery. The following is the inscription on it: — "In memoriam of the Wilson family, who were burnt at the Octagon fire, 8th September, 1879. Robert Wilson, aged 59 years; his wife Sarah Ann, aged 41 years; Frederick, aged 19 years; Robert, aged 10 years; Sarah, aged 8 years; Laurence Oliphant, aged 4 years; also Oliver, died 29th January, 1875, aged 4 years. Weep not for those who have passed from thy side." -Otago Witness, 9/10/1880.

|

| Southern Cemetery, Dunedin |

Local and General

Most readers will not have forgotten the Misses Wilson, who so marvellously escaped the unhappy fate that befell their parents, sisters, and brothers at the much lamented Octagon fire, and how the eldest escaped, comparatively unhurt, after falling from the parapet of the building, and the youngest was saved by the intrepidity of Mr. Grant, of the Dunedin Naval Brigade. We extract a paragraph from a private letter describing how the elder Miss Wilson and some companions received a severe fright whilst employed in the millinery room connected with Messrs Robertson and Moffat's establishment in Melbourne: — "Yesterday (February 21st) I thought I was shot. We (myself and companions) were all sewing, when a dreadful noise was heard, and a flame appeared in front of me which I imagined was a thunderbolt. There was quite a scene — all of us thinking we were shot, or that the wall had fell in. Anyhow our nerves were so unstrung that we all had a good cry. I was nearest the window, and it appeared as if someone had fired a gun amongst us, and a great flash surrounded with sparks quite dazed me. However, fortunately, we were all more frightened than hurt; but, as a man had been killed the previous week by lightning, we were certainly rather alarmed." -Poverty Bay Herald, 30/3/1881.

No comments:

Post a Comment