Benjamin Rudd was born at Walsall, near Birmingham, in 1854. He was apprenticed to a master gardener and in time became a master gardener himself, working for the rich and respectable families in the vicinity.

He saved his money and at the age of 30 took passage on the SS Ionic which, at the tine, was the largest ship to dock in Wellington Harbour, on the way to Port Chalmers.

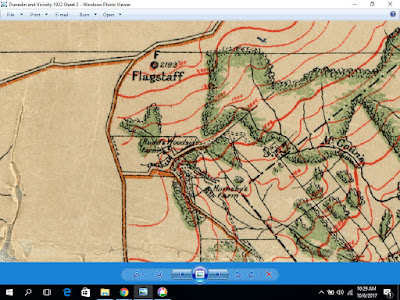

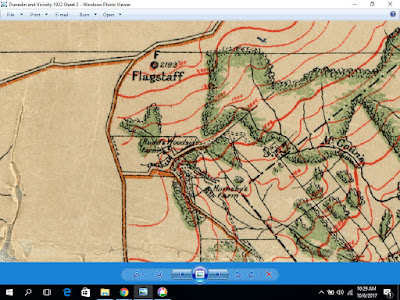

Ben soon found work gardening for the wealthy citizens of Dunedin and bought land on the slopes of Flagstaff, high on the tree line but in a sheltered little area. He took the rocks he cleared from the land and made stone walls that are impressive monuments to his appetite for hard work. He ran stock on his land and his gardening skills were used to turn his patch of hillside into a showpiece of native and introduced plants.

But there was a blight on Ben Rudd's version of paradise - other people. Flagstaff was a popular place for rambling and picnicking in those days and people thought nothing of climbing a fence or wall, finding a pretty spot to sit and gathering firewood to boil a billy for tea over a small fire. Thought nothing, that is, until they met Ben.

Ben took issue with those who climbed and damaged his stone walls, those who damaged his wire fences while climbing over or through them, those who made their fires with the trees he cherished, those who left his gates open and his stock free to wander. He was also less than pleased with those who called him "Uncle Ben."

One of those who used that name had cause to regret it in 1886 when he was riding with a friend up the road to Flagstaff and saw Ben working on one of his stone walls. "Go it, Uncle Ben, you are working hard." he called out as he rode past - "Uncle Ben" was the name Waldie understood to be the one Ben was known by. Ben threw a stone by way of reply and when the horseman - Mr Waldie, a Halfway Bush farmer - turned back to ask why the stone had been thrown, Ben ran for his shotgun and fired it in Waldie's direction, hitting Waldie and his horse, slightly wounding both. Both horsemen then approached Ben for an explanation but, since Ben by that stage was reloading, turned instead for the nearest police station.

When Constable McLaughlin arrived to discuss the encounter, Ben denied using his gun. Then he admitted to firing it but not to hitting his target which had been a long way off. Asked why he fired, Ben said he had been insulted by Waldie - in the resulting trial for attempted murder, Ben stated that Waldie had insulted him many times. His defence counsel stated that the gun was fired to warn off the two men on horses who might have seemed intimidating to Ben - he was not a tall man. Perhaps surprisingly, Ben was found not guilty.

In 1894 Ben was in court again, being sued for assault. One of a party of walkers descending through Ben's land from the top of Flagstaff had his skull fractured by a blow from Ben's pitchfork. The walking party were sure they were within their rights but Ben was sure they were not. Words led to blows and Ben was found liable for 22 pounds in damages plus court costs.

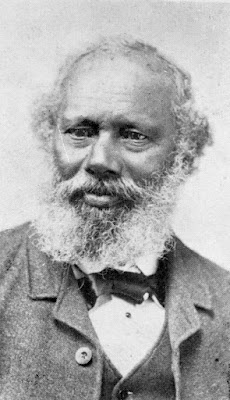

Ben's reputation as the violent hermit of Flagstaff grew and, in 1905, two Evening Star reporters saw a story on the hillside and tried something new in the way of communicating with him. They used courtesy and respect. They called him "Mr Rudd." They asked him if he could spare them some time. They were treated with equal courtesy in return and came back down to Town with a story of "the queer kindliness, the quick, wanton wit, or the shrewd philosophy that live in this Little Grey Man."

The interview began in the usual way of meetings between Ben Rudd and strangers - "a statement of ownership, a request for names and addresses and a descriptive remark about the shortcomings and frequency of trespassers." But Ben soon thawed towards the pair of reporters and the words spoken were "come inside if ye like while I have me bit o' dinner."

They followed Ben into his little house and saw his few possessions - a bible and a couple of other books, a single oil lamp, a side of bacon hanging on a hook, other tools of a simple life.

They were introduced to Ben's only friend in the world, Kit, his old mare. Kit, who would shake hands with children and do other little tricks for their amusement. "Yes, her's been a good 'orse; but 'er's got no teeth and 'er can't eat. Yes; thirty one come November if she lives. An' see 'ere, mister, if her could chew 'er food and keep fit, 'er'd do a day's work with any of them."

|

| Otago Witness, 30/11/1904. |

"Yes, 'er's been a good mare: but I 'as to feed 'er. I makes 'er mash an' gives 'er that. I thought once, I'd best shoot 'er an' end it all. So I made a song about 'er and got photographed with 'er. Mebbe you saw the picture. No? Well, I got it 'ere. I'll show it to ye."

"But the song: what about the song?"

"O, that's there, too. Well, as I tell ye, I got that done, and then I 'adn't the 'eart to shoot 'er. Poor old Kit."

""Do's you'd be done by, that's my religion." said the Little Grey Man...He has queer views, this man of bleak places; but there is shrewd logic at bottom, and through all a poor little pulse of poetry that throbs always against its prison walls of disadvantage. Small sympathy he has for men. To them, mostly he is the savage little despot of the tussock places and the scrub lands; a little uncanny to look on and reputed of great strength and ferocity. But is repute a true delineator? Seldom. And is Benjamin Rudd truly ferocious? No. Suspicious always of his fellows, say some. Maybe; but if so, how did he come to leave two men, acquaintances of an hour, alone in his house while he went paddocks away with a cow and her calf? Just a little odd, a little different from the rest, Ben Rudd is of the Solitary People. Old Kit is his love, and the birds of the air and the beasts of the field are his friends.

"

The men of the Evening Star finally left Ben, still at work and still with more work to do. He had yet to do his most important chore - boiling cabbage and mash for Kit.

The 1905 interview with Ben Rudd is a remarkable document and remarkable insight to a complex, gentle man. The whole of it can be found here.

In March of the next year the Evening Star had sad news to report of Mr Rudd. Old Kit had fallen down one day and did not have the strength to get up again.

"For about twenty years those two had shared solitude; they had been friends with a strange friendship; he had made verses about her, and brewed her hot mash when her teeth left her; and she was used to rub her nose against him and look at him in a way she had. She looked at him when he found her down, and it seemed like the old look. She looked at him, and he looked at her. And so they gave one another their eyes until he made up his mind. He did not try to deceive himself. The page of hope was turned over and smoothed down, and on the other side were just two words.

"And so the Little Grey Man went home and got his axe - his big brown axe with the long, straight, home-made handle. "It was quicker that way," he said; "she might have kicked ten minutes with strychnine."

"In the solitude he saw to her burial, and in solitude he went back to his work and his musings."

Ben remained on the hill, in his solitude, making the occasional visit to town for supplies and also to go to court, still pursuing the occasional trespassing picnicker. He retired in 1919, aged in his mid sixties and sold his farm. He went to live in town, possibly in Roslyn with his older uncle, John Baylie.

But Town was not for Ben Rudd. Before long he had bought land on the other side of Flagstaff, among the tussock, flax and scrub. In a sheltered little pocket, near a small waterhole and far from the lights of the city (though now almost directly under the flight path to Momona Airport) Ben built a stone hut and planted a garden. To build the hut he carried stones for long distances - but that was what Ben Rudd was accustomed to. He spent some time in hospital after being gored by a bull in 1914 but would not have been away from his hillside for long. In 1921 he was reported to be well established "on one of the sunniest and most picturesque spots on the mountain side." and reported as defending his new home as vigorously as his old. In the next year a keen hill walker visited Ben after a fortnight of misty conditions on Flagstaff and found him well but unaware that it was Christmas day.

|

| A visit from Tramping Club members. |

Before long he was being visited by members of the newly-formed Otago Tramping Club who established a territorial truce with him by paying him five pounds in 1923 to cut a track for the Club around the boundary of his property. This was the beginning of a cordial relationship between Ben and the Club.

|

| Ben Rudd in front of his Flagstaff hut - fashion by Army Surplus |

In 1928 "an entry of great interest" at the Roslyn flower show was the potatoes and rhubarb brought in by Ben. He won first prizes for each. Prize-winning produce from a garden in the scrub - truly Ben was still a master gardener.

Two years later time caught up with Benjamin Rudd.

On February 25 Mr and Mrs Stratton of Mornington visited Ben and found him very ill and weak - he'd not been able to fend for himself for some days. Mrs Stratton stayed with Ben while her husband went for the nearest telephone. An ambulance was sent but couldn't make it to Ben's hut. Ben was carried to the ambulance by a police constable who had accompanied it, with the help of some locals. Ben was admitted to hospital - his illness unspecified but presumed to be "old age." He lingered in hospital until March the second.

Memories were shared in local newspapers of "a most picturesque figure with his snow-white beard and hair, short, stooping figure, and clothes mended with string, and even sometimes with flax." Usually he would lead with him his beloved horse, which he was never seen to ride. In his more genial moods "Uncle Ben" would demonstrate this horse's tricks to the school children, making it shake hands and perform many other such tricks. Mention too was made of his ferocity in defending his property from trespassers and his dignity from those who called him "Uncle Ben" to his face.

In 1946, Ben's land on the far side of Flagstaff came up for sale and the Tramping Club bought it, ensuring public access since then. A picnic shelter stands near the site of Ben's hut. His gooseberries and raspberries still grow.

|

| Ben's first home, on the city side of Flagstaff |

Andersons Bay Cemetery, Dunedin.

The last word, here, I give to Mr Benjamin Rudd of Flagstaff - farmer, gardener, gentle man if not gentleman, and poet.

MY OLD BAY MARE AND I

I am a country carrier,

A jovial soul am I

I whistle and sing from morning til night,

And trouble I defy.

I've one to bear me company;

Of work she does her share:

It's not my wife - upon my life!

But a rattlin' old bay mare.

It's up and down this Flagstaff side

The mare and I will go,

The folk they kindly greet us,

As we journey to and fro.

The little ones they cheer us,

And the old ones stop and stare,

And lift their eyes with great surprise

At Ben and his rattlin' mare.

When the roads are heavy,

And travelling up the hill,

I am by her side assisting her,

She works with such good will.

I know she loves me well,

Because the whip I spare;

I'd rather hurt myself

Than hurt my old bay mare.

When the town we reach

She rattles o'er the stones;

And lifts her hooves so splendidly -

Not one of your lazy drones.

It's "clear the road" when Benjie comes:

The crawlers all take care

Of Benjie's cart, the driver's smart,

And his rattlin' old bay mare.

It's Crack! goes my whip,

I whistle and I sing,

I sit upon my waggon -

I'm as happy as a king.

Round goes the wheel -

Trouble I defy -

Go jogging along together, my boys,

My old bay mare and I.

I would not change my station

With the noblest in the land -

I would not be the Premier,

Nor anything so grand.

I would not be a nobleman,

To live in luxury,

I state, if that would separate

The old bay mare and me.

Mr Benjamin Rud and a (possibly) prize-winning cabbage. He wears an old Army tunic, the front skirts presumably tattered by the carrying of stones.