Edmond Slattery came to New Zealand from Ireland for the gold, like so many others. When the gold ran out for the working man Slattery became a swagger. Swaggers were not tramps. They were the essential, moving seasonal workers who were vital to New Zealand farmers. Woe betide the farmer who became known by the swagger community for breaking the tradition of always having a bunk and a meal for a man on his way through the countryside. When harvest time came his farm would be shunned.

Slattery, known as "The Shiner" was a swagger like no other. He was, as John A Lee called him, the "anti-dynamo." His famed ability to trick hard-nosed publicans out of a bottle of gin or a half-crock of whisky made legends grow out of anecdotes and a myth grow out of the legends. Lee's biography of Slattery is kept in the Fiction section of the Dunedin Public Library. Many of the stories were told to John by his father, an old friend of The Shiner.

There's a reason why, in a university, the History Department is in the Arts and not the Sciences.

|

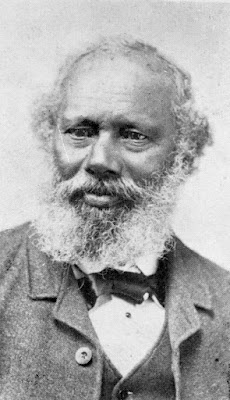

| Ned Slattery and his dog - taken around 1920 |

Slattery's legend has been told by better writers than myself and much of interest is only a Google search away. Here is just one:

On another occasion, when surveyors were busy in the country, and boundaries were not very clearly defined, it is related how "The Shiner" and a number of his mates imposed on a rather too credulous hotelkeeper, whose wit was not a strong point. One fine morning "The Shiner" manufactured a theodolite out of an old alarm clock and three flax sticks for a tripod, and explaining his intentions to his mates, they proceeded to make surveys in the vicinity of the hotel in question, driving pegs in in an indiscriminate way in all directions. When "The Shiner" and company commenced to drive pegs in his garden the hotelkeeper, who had been an interested spectator of the preliminaries, wanted to know what it all meant. 'I am the head surveyor for the Government for this district.' replied ''The Shiner," 'and I am defining boundaries, and I find your hotel is 4ft over the road line. There is no doubt but that it will have to be shifted.' This alarmed the landlord somewhat, and the whirr of the old alarm clock on three sticks, still further alarmed him. 'Is there no way of arranging things with you, Mr Surveyor?' Of course Mr Surveyor was very indignant at the suggestion of his palm being greased, but by means of a few liberal presents to the chief and the members of his party a fresh "survey" was made which was much, more to the satisfaction of the landlord. "The Shiner" is now an old man, but he is still very erect and young in appearance. He has a quiet, humorous look, and hours might be spent listening to his tales. ...

-Anecdotes of tramp life - A C Stevens

I am, however, able to add just a tiny bit to the story of The Shiner - or rather his final resting place. Ned died in the Benevolent Institution in Caversham, Dunedin in 1927. He was buried in a pauper's grave at Andersons Bay Cemetery and a group of Dunedin journalists passed the hat around to raise money for a gravestone. Gravestones are not permitted on paupers' graves. Stories I've read from 2001 and 2009 state that there is no gravestone. But a stone appears in the 2014 photos taken of Dunedin graves and and available on the DCC Cemeteries search site.

A visit to local monumental masons resulted in a consensus - it is a professional job done by none of the masons working today. The installation is not professional. I've read about "guerrilla gardening" - the stealthy adding of plants, usually edible, to plots in public places. Shiner Slattery's stone is an example of "guerrilla monumental masonry." The 2001 story in the NZ Geographic Magazine had the writer finding it appropriate that there was no stone on The Shiner's grave. I think Ned might have chuckled at the thought of someone sneaking a piece of granite in at night.

PS: Since publishing the above, my techniques have changed and I thought it might be worthwhile to see if there was more of interest that I could find about "The Shiner." There certainly was.

At the Courthouse this morning before Messrs Grumitt and Meek, J.P.'s, James Slattery, alias "The Shiner," was convicted of drunkenness and fined 10s, or 24 hours imprisonment. -Oamaru Mail, 22/1/1895.

Ned Slattery, a regular sundowner, who is familiarly known throughout the South Island by the sobriquet of "Shiner," is at present "honoring" Milton with a visit. He was arrested yesterday for drunkenness, and will be brought up at the local court this morning. -Bruce Herald, 4/4/1905.

References in the papers to "The Shiner" have his first name recorded mostly as Edward, though, as can be seen above, he was also James, Edmond, Edmund and, of course, Ned.

THE COURTS-TO-DAY

CITY POLICE COURT. (Before H. Y. Widdowson, Esq., S.M.A Drunkenness. — A first offender, who did not appear, was fined the amount of his bail (10s). Another first offender was fined 5s. Edmund Slattery (who was described as a bird of passage, well known of people as “The Shiner”) pleaded guilty to drunkenness, and promised not to bother the police again. — He was convicted and discharged. -Evening Star, 26/9/1910.

An interesting personality turned up on a charge of drunkenness at the Dunedin S.M.'s Court the other day, in the person of Edmund Slattery, better known as "The Shiner," who has a reputation throughout the country as a confirmed occupier of the dock. Edmund is now seventyone years old and is getting a bit deaf, which caused him to make a rather funny reply to Magistrate Widdowson. The S.M. asked Edmund what work he had been doing recently, to which the latter replied: "Oh, either whisky or brandy." Edmund was finally convicted and discharged, on the understanding that he would never come to court again. -NZ Truth, 1/10/1910.

At the City Police Court, Dunedin, on September 29th, Edmund Slattery, who gives his age as 71 years, and who was described by Sub-Inspector Phair as a bird of passage, more familiarly known as "The Shiner," was convicted and discharged for drunkenness. Old Charlestonians will recollect Slattery as storeman for Hehir and Molloy in the sixties, and as a prominent leader at the agitation in connection with the prosecution of Allen, Larkin, Gould and O'Brien for the shooting of Constable Brett at Manchester. -Grey River Argus, 3/10/1910.

Local and General

Edward Slattery, 76 years, familiarly known throughout Southland, Otago, and Canterbury as "The Shiner," appeared in Court at Invercargill on Tuesday to answer a charge of being idle and disorderly, in that he did solicit alms. Senior-sergeant Burrowes, who had known the accused since '76, led the prosecution in no uncertain manner by declaring that Slattery was a typical "sundowner" and a champion work-dodger. He had solicited alms of Constable Anderson on the East road the previous day, which action was what had brought him there. Defendant stoutly maintained that he never had begged. People frequently offered him money, but he refused it. Besides, he had £l4 in safe custody at Gore. The case was adjourned until the afternoon to enable inquiries to be made regarding the money. On resuming the police reported that the cash was nowhere to be found, and the Bench extended to the accused the King's hospitality over a period of three months "hard." Slattery confessed that be "didn't expect to have to do time," and asked if he could call at Gore for his money "on the way down." The presiding J.P.s jestingly gave the desired permission, and added that if the defendant did have money it only blackened his offence of begging. -Nelson Evening Mail, 1/12/1916.

Police Court

“THE SHINER.”

Edward Slattery, said to be eightyseven years of age, pleaded guilty to being found drunk. — The Senior Sergeant said that defendant had not been before the court since 1923. He was a very old man, and a tramp well known in the Taieri district as “The Shiner.” — The Magistrate: “There is nothing known against him?” — The Senior Sergeant: “No, sir; only drunkenness.” — Defendant was convicted and discharged. -Evening Star, 27/2/1925.

“THE SHINER”

PASSING OF A CELEBRITY

[Written by B. Magee, for the Evening Star.]

The death of Edward Slattery (better known as “The Shiner") aged eightynine years, at the Benevolent Institution, Dunedin, removes one of the most picturesque figures from the highways and byways of this province, and in an especial manner from North Otago. Men of middle age can look back to their boyhood and visualise the romantic personage about whom clustered many strange and humorous stories; while men in the sere and yellow leaf recall the handsome, upstanding, raw-boned Irishman in the heyday of his youth, when life was freighted with golden dreams and gay anticipations.

“The Shiner’' apparently had in his complex an unexpurgated vestige of a race once regarded as a human institution in Ireland. Up to the middle of the last half century, newspapers were few and far between, and the conditions under which the people lived in Ireland made them dependent for news of how the world wagged on a race of nomadic men and women, who roamed about the Green Isle, conveying the news to the lonely dwellings scattered throughout the country and the mountain fastnesses.

It is quite needless to say that the tribe who lived by this means were welcomed with that cordiality for which Ireland is so famed. An honored place by the fire, an attentive audience, payment in the shape of a plethora of homely food, and a comfortable lodging for the night were the rewards those people expected and received. Readers of Will Carlton’s stories will recall the type in ‘Mary Murray, the Match-maker.’ For the arranging of matches between the boys and colleens widely separated by distance, came within the provide of the race’s activities. The kitchen of an Irish household is described as the shadows lengthen and the landscape is becoming veiled in sleep. In rushes one of the little spalpeens of the family, yelling:

”Mother, mother, here’s Mary Murray comin’ up the boreen (short road)!”

“Get out awick: no she's not," replies the mother, with half suppressed pleasure.

“Bad cess to me, but she is; that I may never stir if she isn’t. Now!” replies little Patsy.

The whole family are thrown into excitement by the welcome intelligence that Mary is coming up the boreen. When she arrives at the door she is hurried to the place of honor by the hob, to the accompaniment of such expressions as;

“A hundred thousand welcomes, Mary.” “Och, Mary, musha, what kep’ ye away so long?” “An’ what news, Mary? Sure you'll tell us everything, won’t ye, now?”

Mary tells them everything that happened, and probably a good deal that didn’t. How death had overtaken this one. The intelligence received from faraway New Zealand or Australia, of how some of the young people who emigrated were rising in the world. How such a marriage she had brought about between a boy in one end of the country and a colleen in the other was one long unbroken honeymoon. How another — in which Mary had no hand - did not turn out well — besides, as she said, “there was always a bad drop in the Haggerties.”

Nurtured in such an environment Ned Slattery must have aspired to join the tribe of news gatherers and disseminators, an indolent nature assisting thereto, for “The Shiner” was work-shy, though it is said, that when needs must, “The Shiner” was capable of rising to the occasion and doing good day’s work. In the early days of settlement in New Zealand he must have found conditions akin to those he had left in his native land — people living away from the means of hearing what was going on in the world outside. Apparently “The Shiner,” for a time, found his calling welcome in the far-scattered communities, and thus he continued a custom in the new land which was long established in the old. Time and a changed environment altered conditions to such an extent that he found his occupation, like that of Othello’s, gone, never to return. But his habit of wandering over the country on foot became fixed and unalterable as a primary law of nature. The vagabond life “The Shiner” led has a strange fascination to most of us, for we are all at heart vagabonds and have a hankering after the open spaces like Cavalier and Roland of old, with the sky for a tent and no other bed but mother earth.

So what does it matter if time be fleet,

And life, sends no one to love us?

We’ve the dust of the roadway under our feet.

And a smother of stars above us.

“The Shiner’s” peregrinations took him at times beyond the bounds of Otago and Southland. He was well known on the West Coast in the early days, and many a good story is told of his stratagems to evade the primal curse. A strange trait in his character was his honesty — with qualifications.

The Ten Commandments, in his philosophy, were never designed to protect publicans, and on occasions they might be waived where stony-hearted farmers were in question. Publicans had preyed on “The Shiner,” and logically he might prey on them. On one occasion he lived sumptuously for quite a considerable period at the expense of a West Coast publican. Posing as a Government inspector of buildings, he directed Boniface’s attention by measurements to the fact that his hotel was encroaching several inches on the road line. Much correspondence ensued between “The Shiner” and hard officialdom of Wellington, but despite the sympathetic attitude adopted by the pseudonym inspector, the authorities insisted on the building being shifted back to its proper alignment.

During the negotiations “The Shiner" dined on rich fare and partook liberally of the copious libations poured out by the alarmed publican. Ultimately “The Shiner,” like Moses of old, struck the hard rock of officialdom, in Wellington, and there issued forth a stream of mercy for the distressed hotelkeeper. The “inspector” conveyed the joyous news to the hotelkeeper, and with many blessings on his head, “The Shiner” fared forth into the world for fresh adventures.

No one ever saw “The Shiner” in a hurry. He moved along with dignified mien, arms folded or clutching a stick over his shoulder, to which was attached all his portable property wrapped in a colored handkerchief. Church functions had a great fascination for him, and the greater the display of ecclesiastical purple, the greater the magnetic power it exercised over the wanderer. Indeed, the last big function, at which the whole of the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church in New Zealand assembled, the opening of Redcastle College at Oamaru, saw “The Shiner” fraternising with the prelatical big wigs.

Sports gatherings, too, had an attraction for him, and in the heyday of his manhood he was frequently a competitor in the Irish Jig, which he danced as only an Irishman could dance it, with refinements and embellishments that have been grafted on in modern times severely eschewed. His arms worked, hobnail boots beat a lively clatter, legs were thrown out at right angles to his body — of course — and the vim he infused into his performance sometimes won the favorable decision of the judges. On such joyous occasions “The Shiner” sometimes let himself go, with the result that he spent a few nights under a roof that kept out the rain; his usual nightly bed being wherever he hung up his hat at nightfall — in old disused buildings, in caves in the hillsides, under hedges, burrowed into haystacks, and out in the open fields.

On one occasion, when he overstepped the bounds of strict sobriety, “The Shiner” found himself the following morning looking from the dock at a countryman of his — a member of the Great Unpaid — perched in the magisterial bench. The J.P. was a bit of a character in the small Otago town where he ran a fancy goods store. Among his stock in trade was a great assortment of dolls, and much of the J.P.’s business consisted in retailing those to the budding maidens. The J.P. looked very sage and important in his exalted position, as he viewed with severity the delinquent before him. He admonished him on the baleful effects of over-indulgence in strong drink, to which admonition “The Shiner” listened, with scorn governing the motion of his curling lips. Forty-eight hours without the option was the price “The Shiner” had to pay for his hectic night.

At the expiration of his term, when a constable set the captive free, he marched round to the gaoler’s office with arms folded and head thrown back, and to that astonished official put the question in a contemptuous tone of voice:

“Can you tell me where John, the doll-dealer lives?’’

And without awaiting a reply, he turned on his heel and majestically strode out to freedom. Whether he looked up the J.P. doll-dealer to square accounts is a point on which history is dumb.

To “The Shiner” the past was an encumbrance, the future a superfluity. “Sufficient for the day.” was his philosophy. North, south, east, or west was all the same - his only concern was where his next meal was to come from. Many stories cluster round the nomad, perhaps not all apocryphal, but he was the type of man whom they fitted. On one occasion it is recorded that he was undecided the particular road he would take, as he sat in the public house bar. Taking off one of his boots, he pitched it through the front door. The direction the toe pointed decided the route for the day’s tramp.

As has been said, “The Shiner’s” pet aversion was work. At times, however, when the fount of farmers’ and townspeople’s generosity would dry up, it was a dire necessity. He was reduced to seeking a job on one occasion. A “cockie” engaged him on contract to dig a well. The job was tackled manfully, and when he got down the required depth, he scrambled out exhausted to survey the job. While he did so the sides fell in, and he saw by the terms of his contract the necessity of repairing the mischief that a malign fate had done. “The Shiner” pondered the situation, and his mind reacted to the demand made on it. Placing his hat and coat carelessly by the side of the collapsed well, he retired to the seclusion of a clump of hushes. Soon a farm hand happened along, and, seeing the collapsed well and "The Sinner’s” habiliments lying alongside, he raised a hue-and-cry. From all parts men hastened and heroically put their best into the work of digging out the well in order to recover the body. Finding nothing at the bottom of the well the men got out and mopped their perspiring faces. The ruse having succeeded, “The Shiner” rose from his hiding place, went over to the well, inspected it, complimented the farm hands on the job, went to the farmer, collected his fee, and stately strode off to the next township.

“The Shiner” appeared to have no relations. He was always a solitary individual. He knew thousands intimately, and almost everybody in the country he traversed for generations know him. Yet he was always alone on his tramps. For some time he had been in the Old Man’s Home, at Oamaru, but the ingrained spirit of restlessness would occasionally prove too strong, and he would forsake the comforts of the home for another hike across country.

For several years his friends saw the end of “The Shiner’s” long road growing nearer. The handsome and commanding figure had shrunk, and the buoyant step had long lost its spring. The bizarre modes of dress affected in his younger days persisted to the end, though they more resembled the dropping sails on a much battered derelict vessel slowly drifting to its last port.

The burden is too heavy for the back,

The road too rough for all my strenuous trying;

And all along the worn and withered track

The flowers I used to see are dead and dying.

Peace to his ashes. -Evening Star, 20/8/1927.

FORGOTTEN MEN

TO THE EDITOR OF THE PRESS

Sir, — I listened-in on the "Man in the Street" session a couple of weeks ago to a brief but deeply interesting review of old-time pioneers who built the roadways for others to walk on in comfort and security, but who themselves were hot successful in ambitious struggle for fame and power, and whose lot was cast in squalid and hopeless drudgery and weary, low-paid toil. As a farmer's son and later a farmer myself, "Uncle Scrim's" reference to some of these one time well-known wanderers of the road touched a chord of remembrance of youthful experience and personal contact with at least some of the names quoted. First and foremost, Ned Slattery, "The Shiner," a beloved memory in many a way-back home, with his fund of wit and humour, ever ready to regale his hosts with tales of his unique exploits, and able to discourse on almost any subject from the Koran to the Bible, from Aristotle to Shakespeare, from the sagas of Norway to the fairy tales of Ireland. He would hold his audience enthralled. A nobleman of nature, highly educated, deeply religious, clean living, masterless and unmasterable, loyal to his friends, who were legion, and loved by even the dogs who barked him a welcome as the farmers' children ran to meet him.

Then there were the "Galway Blazer" and the "Prince of Wales," two other well-known and well-liked walkers of the roads, who, too, had many friends, friends who were real and could see deeper than the outer garb, the artificiality that so often cloaks a crooked, cowardly, cunning mind and soul in the body so impeccably and respectably dressed.

What a pity we did not then have, as we have now, a humane government to tend for and care for these poor old worn-out toilers, who had laboured to fatten the rich, yet failed to enrich themselves! They lived a hard life of privation and neglect, toiling hard for poor pay and poorer fare. Who could blame them if, in their hopelessness, some of them lost a trifle of society's polish and veneer? Yet they each and all carried hearts of gold beneath their threadbare coats. Reaping and tying by hand, opening and delving in shingle pits; building sod fences — back breaking, body-racking, life-sapping labour in the rain and cold of winter (the only time it could be efficiently done) draining swamps, and felling bush, what chance had these poor human beasts of burden of amassing wealth or station in society, or fame in history's annals? Most of them who are still alive are to-day inmates of our old men's homes, broken wrecks of humanity, dependent on the charity of a generation who enjoy the comforts their sweat and toil provided for a people who know them not. Would it not be a Christian and humane act of justice on our part, we who have reaped the fruits of their labour, their sweat, and endeavour, if we this coming Christmas, say, see that they get gifts such as a little pocket money, extra tobacco, a trip to the seaside, the pictures, a picnic, or any form of change or amusement that would appeal to them, and make them feel in their already numbered days that life for them has not been altogether in vain? Should any public-minded, humanity-loving citizen or benevolent society be interested in my suggestion, I will be only too pleased to subscribe to such a worthy and worth-while cause. In conclusion, may I quote a few lines of a poem "The Shiner" taught me as a boy: —

Speak history who are life's victors

Unroll thy long annals and say

Are they those whom the world calls the victors

Who won the success of the day?

The martyrs or Nero? His judges or Socrates?

Pilate or Christ?

—Yours, etc., LET US REMEMBER. Hornby, November 22, 1938. -Press, 26/11/1938.

BELOVED VAGABONDS

DAYS OF SWAGGING RECALLED

“Shining with the Shiner,” by John A. Lee, D.C.M. (Bond’s Printing Company, Hamilton; 5s, post paid.) — Reviewed by W. Downie Stewart

This is a new book by Mr John A. Lee, who has already written five books, the most notable of which was “Children of the Poor,” described by Bernard Shaw as a "whopper.’’ Another of his books, “Civilian into Soldier,” was declared by a leading English periodical as the “best war book.” In this new volume Mr Lee has sought to recreate in a series of anecdotal chapters the portrait of a famous New Zealand swagger known as “The Shiner,” who lived by his wits and whose exploits have become almost legendary. Many people still alive knew “The Shiner,” whose real name was Ned Slattery. Mr Lee, who himself as a youth tramped the roads of Otago and Canterbury in every direction, says in his interesting introduction: “I knew a lot of the men of the road. I walked 30 miles side by side with ‘The Shiner’ in South Canterbury, so I have footed it with one of the most glamorous of our vagabonds.” He is of opinion that the day of the swagger is past, and that he will walk no more, partly because of social security, and partly because of the disappearance of the big stations that required a seasonal army for harvesting, shearing, and rabbiting. He does not regard the thousands of men who tramped the roads “in the giant depression of 1931-33” as swaggers — they were merely men out of work. His conviction that the swagger and the man out of work are things of the past may be sound if social security is sound — but there is and can be no such thing as security in this world.

Although Mr Lee's introductory sketch of the swagger as a figure in our social history covers only six pages, in my view it is one of the best things he has ever written and will be invaluable to any future historian who does for New Zealand what Trevelyan has done in his "Social History of England.” The chapters which relate humorous episodes in the wandering life of “The Shiner" and his mate, “the Honourable MacKay" McKenzie, known as "the Highland chief,” and others are all vividly written. Mr Lee knows how to make his characters talk in the true language of the back-block “pub" bar and the swaggers’ camp, and there is pathos as well as humour in his stories. The only unpleasant incident in the book is the Honourable MacKay's habit of dropping his glass eye into other men's beer glasses, knowing that they would then reject the beer, which he promptly drank. But Mr Lee has been wholly successful in re-creating "The Shiner" and the life of the swagger fraternity. He had the wisdom, when broadcasting some years ago, to give a series of talks about swaggers, and this brought him hundreds of interesting letters, which now form what he calls “an amazing record of pioneering and vagabond reminiscence." He is still collecting such letters for the use of future writers. How true it is that the artist finds rich stores of material wherever he looks, while some young writers complain that they cannot find anything to write about! For my part. I can acquiesce in Mr Lee’s exclusion from politics without any profound regret if it means that he is going to write more books; these will bring him more permanent fame than he can hope to gain by building his house on the shifting sands of politics. -Otago Daily Times, 6/1/1945.

So much for "Papers Past" references to "The Shiner." A search for "Edward Slattery" produced many results, though the young man from Palmerston North of that name who died while tree felling was obviously not our man. Several court appearances for drunkenness in the Otago region in the 1890s and into the next century were more likely him, including one which made reference to one Edward Slattery being provided liquor while under a prohibition order.

Peace to his ashes.

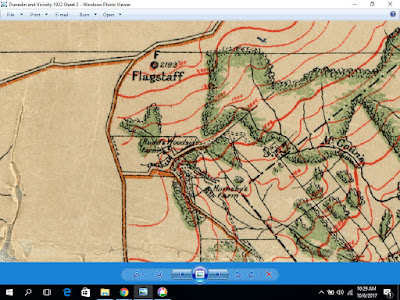

But Town was not for Ben Rudd. Before long he had bought land on the other side of Flagstaff, among the tussock, flax and scrub. In a sheltered little pocket, near a small waterhole and far from the lights of the city (though now almost directly under the flight path to Momona Airport) Ben built a stone hut and planted a garden. To build the hut he carried stones for long distances - but that was what Ben Rudd was accustomed to. He spent some time in hospital after being gored by a bull in 1914 but would not have been away from his hillside for long. In 1921 he was reported to be well established "on one of the sunniest and most picturesque spots on the mountain side." and reported as defending his new home as vigorously as his old. In the next year a keen hill walker visited Ben after a fortnight of misty conditions on Flagstaff and found him well but unaware that it was Christmas day.

But Town was not for Ben Rudd. Before long he had bought land on the other side of Flagstaff, among the tussock, flax and scrub. In a sheltered little pocket, near a small waterhole and far from the lights of the city (though now almost directly under the flight path to Momona Airport) Ben built a stone hut and planted a garden. To build the hut he carried stones for long distances - but that was what Ben Rudd was accustomed to. He spent some time in hospital after being gored by a bull in 1914 but would not have been away from his hillside for long. In 1921 he was reported to be well established "on one of the sunniest and most picturesque spots on the mountain side." and reported as defending his new home as vigorously as his old. In the next year a keen hill walker visited Ben after a fortnight of misty conditions on Flagstaff and found him well but unaware that it was Christmas day.