Think of a torpedo boat these days and you might think of a lightly-built, fast small craft, prominent in the Second World War, carrying torpedoes (originally referred to as "locomotive torpedoes" to differentiate them from the original meaning of the word, which applied to that which we would now call a naval mine) and charging at full speed against a much larger vessel.

In the 1880s things were different. The torpedo used by a torpedo boat was the type known as a spar torpedo. It was basically a pole attached to the bow of a small, fast boat with an explosive charge on the end. Its use was simple - steam at full speed towards a ship and ram the spar into its side, embedding it in the target's hull. Then reverse, hopefully triggering the explosives. All while being fired at, of course.

The HMS Taiaroa arrived in Dunedin from London in February, 1884. It was one of four bought by the NZ government. They were powered with a two-cylinder reciprocating steam engine rated at 173 hp (123kw) making for a top speed of 17.5k (about 50km/h) As well as the spar torpedo they had a two-barrelled Nordenfelt quick-firing gun of 1 inch calibre.

Seven brave men were their crews.

SHIPPING

A trial trip of the torpedo-boat was made yesterday. From Deborah Bay to the Jetty street wharf, a distance of about ten miles, was done under very easy steam. In thirty-two minutes, and from town to the Port against a head wind and adverse tide in forty minutes. She also made a run to the Heads against a fresh wind and confused sea, displaying excellent sea qualities. Her boilers had a pressure of 901b to the square inch, and the engines averaged 250 revolutions per minute. Though the conditions were unfavorable - the machinery having been dormant for years, and an inferior coal was used - the trial is considered to have been thoroughly satisfactory. The vessel is to be fitted with appliances for the Whitehead torpedo. Mr Ward, the torpedo instructor, was in charge, and was accompanied by Major Goring, and Messrs Hackworth and Chamberlain, of the Customs. -Evening Star, 18/3/1886.

THE DEFENCE WORKS (excerpt)

DUNEDIN GOSSIP (excerpt)

OTAGO ANNUAL REGATTA (excerpt)

The torpedo demonstration was one of the principal attractions of the day and was thoroughly successful. The only drawback was that there was nothing to attract attention to it, and consequently a number must have missed it, since it occupied only a few seconds of time. The boat which was to be destroyed had been bought for the purpose. Two masts were rigged in it, and to make the thing more realistic, dummy men were placed on board the doomed vessel. Promptly at two o’clock, and while the attention of most spectators was held by the finish of a rowing race, the noise of an explosion was heard, and a large column of water was seen to rise in the air, a white frothing mass. When the commotion subsided nothing but fragments of the boat could be seen floating on the discolored foam. This demonstration was undertaken by Lieutenant Lodder, the torpedo instructor, assisted by the Torpedo Corps and Navals. -Evening Star, 27/12/1888.

SHIPPING

The torpedo boat no. 169 steamed up from Port Chalmers yesterday forenoon, and after embarking Captain Falconer, Mr Blackwood (Government inspector of machinery), and others ran down to Deborah Bay, returning to Dunedin in excellent time. The little vessel (already reported upon by us) appeared in perfect order. -Otago Daily Times, 18/4/1890.

LATE ADVERTISEMENTS

DISTRICT ORDER, Militia and Volunteer Office, Dunedin, March 9, 1891.

The Port Chalmers Naval Artillery Volunteers will furnish a Firing Party of 13 Rank and File under command of a First-class Petty Officer to attend the Funeral of the late Torpedoman W. Densem, of the Torpedo Corps, Permanent Militia. The Party to Parade at the Garrison Hall, Port Chalmers, at 3.45 p.m. on WEDNESDAY, 11th inst. The Port Chalmers Band is requested to attend, and Officers and Members of Volunteer Corps in the district are invited to assemble at the Dunedin Railway Station at 2.15 p.m.

H. W. WEBB, Lieut.-colonel, Commanding District.

___________________________________________________

THE MEMBERS of L BATTERY, N.Z.A.V., are requested to Parade at the Garrison Hall, Port Chalmers, on WEDNESDAY, 11th Inst, at 3.45 p.m. sharp, to attend the Funeral of the late W. Densem, Torpedo Corps.

Full dress, white gloves, and side arms.

W. J. WATERS, Captain.

____________________________________________________

PORT CHALMERS NAVAL ARTILLERY VOLUNTEERS.

THE COMPANY will Parade at the Garrison Hall on WEDNESDAY, the 11th inst., at 3.45 p.m. in order to attend the Funeral of the late Torpedoman William Densem, of the Permanent Torpedo Corps. Uniform and side arms only.

T. J. THOMSON, Capt., Port Chalmers Naval Volunteers.

Naval Orderly Room, Port Chalmers, March 10,1891. -Evening Star, 10/3/1891.

THE GUN COTTON EXPLOSION AT SHELLY BAY.

In the 1880s things were different. The torpedo used by a torpedo boat was the type known as a spar torpedo. It was basically a pole attached to the bow of a small, fast boat with an explosive charge on the end. Its use was simple - steam at full speed towards a ship and ram the spar into its side, embedding it in the target's hull. Then reverse, hopefully triggering the explosives. All while being fired at, of course.

The HMS Taiaroa arrived in Dunedin from London in February, 1884. It was one of four bought by the NZ government. They were powered with a two-cylinder reciprocating steam engine rated at 173 hp (123kw) making for a top speed of 17.5k (about 50km/h) As well as the spar torpedo they had a two-barrelled Nordenfelt quick-firing gun of 1 inch calibre.

Seven brave men were their crews.

ON BOARD A TORPEDO-BOAT.

During the last two days Captain Fairchild and the chief engineer of the Hinemoa have been trying one of the two torpedoboats lately imported. On Wednesday the engines were in capital order, and quite a crowd of members and other people got ready to make a trip. There was a fair amount of wind and sea, so, as the little, venomouslooking thing dashed away towards the Hutt, she sent the spray flying right and left, and showed the pretty salmon-color, with which she is painted below the water, very plainly. This first trip lasted nearly an hour, and the return journey from Petone was done in just twenty-one minutes. The distance is something more than six miles, so that the speed was about eighteen miles an hour. All the exigencies of a modem war vessel do not include carrying passengers, those who went clung on anywhere about the deck. and braved smoke and salt water in the most heroic manner; in fact, they came back looking like men who had been down a flooded coal mine. On the second trip, at mid-day, everybody who could borrow an old hat and a long macintosh did so, and he who could "raise" a pair of "over-alls" from some sailor friend or other was reckoned a lucky fellow. Captain Fairchild, all smokebegrimed, and black-faced, takes his stand along the little steering turret to direct operations, and off we start. Even in the smooth water a passage by the torpedo boat going on at half speed is a novelty in the way of travelling. To borrow a phrase or two from short distance running, she gets on way from the scratch in a manner which astonishes one. She would make an out and-out "sprinter" but it is when the Engineer turns on a full head of steam that the voyage becomes actually exciting. The little boat has been slipping through the water fast enough before, but now, on a sudden, seems endowed with life, and goes off almost with a leap, vibrating and pulsating all over like a sentient being, at a racing pace, which almost takes your breath away. The whole sensation is so novel, and the boat’s deck is so close to the water, that you absolutely seem to be rushing "through" instead of over the sea, which dashes and roars all round you; in fact, as a member very pithily put it: "It’s like a ride on the back of a dolphin." Behind her the sea seems to be pressed down by the quick passage of the little steel monster over it, and a great wake of foam is raised which comes rolling after you. For a short while we showed off our paces to an admiring crowd on the wharves, flying about and turning in small circles, the boat answering to her helm in a marvelous manner, and the beautifully finished engines, at that terrific speed, working like clockwork. Then, after a smart run head to wind along the shore past Ngahauranga, Captain Fairchild put about for Evans Bay. There, as we sped past the stores by the patent slip, at almost the rate of a railway train, the whole population turned out, the women folk waving handkerchiefs in a most excited manner. Having afforded them food for wonderment and small talk enough for this week, we spun round in a circle and shot away for home again. The signal that the Hawea was in sight was flying, and the sporting members fried hard to persuade Captain Fairchild to go out to the Heads and run "rings round her" as she came up the harbor, but the engineer’s clockwork wanted attending to, and he was inexorable, so back we went, sometimes at half-speed, and sometimes making a spurt that sent the spray flying over us. The whole thing did not take more than fifty 7 minutes, and in that space of time we must have covered fourteen miles. The boat is wonderfully seaworthy, and, it not driven at more than nine or ten knots, takes the seas like a duck. Captain Fairchild is so charmed with her that, as one has to go to Auckland, he proposes to steam up there in her, of course choosing fine weather.— Lyttelton Times. -Evening Star, 24/10/1884.

TELEGRAMS

AUCKLAND

A series of successful experiments in torpedo practice were carried out to-day in the torpedo boat in the presence of Lieut. Archer, Colonel Lyon, and Major Shepherd. Captain Morrison's spar torpedoes were the first used, and afterwards submarine wire. -Oamaru Mail, 17/7/1885.

TORPEDO BOAT BUILDING.

(Daily News,)

Until men begin to beat their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning hooks, there must always be a profound interest attaching to such work as that in which Messrs Thornycroft and Co. are engaged, on a pleasant bend in the river, just under Chiswick Church. It is an intensely interesting and highly-important work, albeit one cannot but feel that it is rather a cruel fate that has caused the outbreak of this dreadful din of warlike preparation in this otherwise quiet and secluded corner of the world. One gets at it by burrowing down narrow thoroughfares amid old-fashioned houses and old-fashioned gardens, full of the flowers which were in the fashion a couple of generations ago. Down in this corner of Greater London there are ivy-clad buildings and time-honoured trees and crumbling brick walls capped with snapdragons and wallflowers, and from the bottom of some of these old world lanes one may get glimpses of the river shimmering under willows just now arrayed in the brightest of their spring foliage. There are nooks and corners here, plenty of them, in which one might appropriately sit and look out upon the river and smoke a churchwarden clay, and listen to a wooden-legged pensioner spinning yarns of the doings of our old wooden ships. One gets down as far as the church and then begins to think that somehow he must have come wrong. It can hardly be down in this sunny, sleepy corner that a thousand men are working night and day in the building of torpedo boats. But yes, here they are, close at the back of the handsome little church, whose venerable tower looked out over stream and meadow for many a long year before the world began to dream of ironclads or torpedoes. Down here in this quiet nook the Messrs Thornycroft have wheedled placid old Father Thames up into their trenches, and they have thrust out huge galvanised iron sheds over his brim, and they have set up a din of hammers and a roar of machinery and a blast of bellows which render it almost indispensable to be master of the deaf and dumb alphabet if any conversation is to be carried on while getting about their place.

Out of this bend of the Thames there have been going for some years past now a constant series of the most murderous little craft that the wit and ingenuity of modern times have been able to devise. They have just now handed over to the Admiralty, at Portsmouth, one of the largest and most destructive, vessels of the kind ever yet built. It is 113 ft long, and 12ft 6in in beam, and it will run at about 20 knots an hour. In the bows are two tubes, each to be charged with a Whitehead torpedo, and in the stern of the boat is another tube for another torpedo, which can be discharged in any direction while the vessel is going at full speed, and which, it is said, will with almost absolute certainty hit a ship at 200 or 300 yards distance. It is also armed with a Nordenfeldt gun with nearly an all-round fire. This vessel is now at Portsmouth. There is another one lying in the yard now, which was built last year. It will presently steam down the river almost unnoticed probably; yet if it were recognised and were known to be charged with its deadly missiles, its mere presence among our mercantile shipping might well create something of a panic, even though there was no probability of its letting one of its thunderbolts slip. Our Government has just ordered 20 torpedo-boats of this firm, which is now working night and day on the shallow draft-boats for Nile service.

It is of course the boats only that are built here. At Chiswick they have nothing to do with explosives, and the reason that this peculiar business has taken up its quarters in this peaceful reach of the Thames is that this firm some years ago acquired a reputation for fast steam yachts. They are the patentees of a peculiar form of screw giving great speed and specially well adapted for vessels of a light draft. This screw, together with well laid lines and powerful small compound condensing engines, has afforded the means of turning out just the vessels for torpedo service — Liliputian in size and Herculean in strength. It is now some seven or eight years since torpedo boats were first ordered by the British Government from this yard, which since that time has impartially sent out its boats to pretty nearly all the nations under heaven, and is now recognised as one of the most important factories of this peculiar kind of craft. Torpedo boats are entirely made here except as to the rough castings. They are brought down from the north of England and what actually goes on here is an immense amount of drilling and forcing and fitting and so fourth, and of course the actual fitting up of the vessels. There are immense workshops, in which powerful drills and punches and rivetting machines and shears are boring and clipping and squeezing about iron plates and bars as though they were made of cardboard or putty. All over the place smiths are at work at forges, and the din of hammering is something distressing to unaccustomed cars. In the actual work, however, there is, of course, nothing very especially worth notice. It is the vessels as they come out finished that present the only objects of peculiar interest. The 20 boats ordered by the Government are different from the one just delivered at Portsmouth. They are to be what are known as "spar torpedo" boats — frightful little desperadoes that rush right up to an enemy's vessel with a torpedo about twice the size of a man's hat, and with 40lb of dynamite or gun cotton inside it, stuck at the end of a spar thrust out from its bows. This spar is of steel in three pieces rivetted together. It lies along the deck ordinarily, but on the approach of an enemy a windlass is brought into action, and a wire rope is coiled and the pole thrust out over the bows and dipped down so as to hold the torpedo about 20ft in advance of the bow and 9ft below the surface of the water. Any vessel unlucky enough to meet one of these little spitfires thus prepared has only to touch the torpedo and, unless it be of unexceptional construction, down it must pretty certainly go, or, if the impact is not actually made, the officer on board the torpedo boat can fire it at discretion by electricity by merely pressing a key. Of course it is not always that one of these little dare-devils can get at a ship, at close quarters, and for torpedoes the charge for explosion is not great. If it were a heavier charge it would probably destroy the torpedo boat as well as the vessel attacked. "But," says Mr Donaldson in a paper read by him before the British Association some time ago, "it is a question whether it would not be a mere prudent and certain course to use the spar torpedo in circumstances like those which obtained at Alexandria the other day, when the attacking ships were so enveloped in smoke that the firing had to be suspended till the smoke cleared away. The midshipman in the top might have seen boats 400 yards off — the distance from which a Whitehead torpedo might have been launched at the vessel below the said midshipman — and might have directed the machine gun fire upon them, but close in it is a question if he could; and it would be easier for the commanders of the torpedo boats to find an opening for a spar torpedo than to direct the course of a Whitehead in the mass of smoke with which they and the enemy would be surrounded." This may serve as an illustration of the purposes, to which spar torpedoes may sometimes be put. Those just ordered by the Government, it should be added, are to have on their decks, in addition to the spar, a Hotchkiss gun, capable of shooting out explosive shells pretty nearly all round the compass. The shells are designed to cripple or destroy the enemy's torpedo boats. They will pierce their bulletproof iron casing, and must be particularly nasty visitors inside one of these closely packed little craft.

These small spar-boats are, however, in point of deadly power, not to be compared with those which, like the one sent out from this yard on Thursday, and the one lying there now, are capable of shooting out their messengers to a distance of 400 or 500 yards. The boat up there on the stocks now is a particularly interesting subject. It is a long narrow craft, clad in an iron coating, sufficiently thick to keep out bullets, though penetrable by the missiles of machine guns such as the Nordenfeldt or the Hotchkiss. It is divided throughout its length into seven or eight watertight compartments, which in action would each be closely shut in from the rest of the vessel. If, therefore, a hole were made in any one of them, and it filled with water, it would not sink the boat. In the engine-room there is an especially ingenious provision against any mishap involving the bursting of one of the steam pipes. As the engineers when the boat is in action would be shut down close in their own watertight compartment, the bursting of a steampipe would involve the death of the men by a horrible process of scalding. In these Thornycroft boats there is a small iron door in the roof of the engine-room, which, under the increased pressure of the escaping steam would blow open automatically. The torpedo chamber is, of course, in the fore part of the vessel. There are two huge tubes lying parallel with the keel of the boat, and connected with these is a deal of complicated machinery. Into these tubes the Whitehead torpedoes — frightful packages of explosives and machinery, some 14 or 15 inches in diameter, and from 14 to 19ft long — are thrust and shut in, and then the air in the tubes is condensed till it has a pressure of about 100 atmospheres. Of course, the torpedo is discharged by opening the front of the tube, when the outward rush of the condensed air carries the torpedo with it. The thing pursues a steady course under water, propelled partly by the momentum imparted to it from the tubes and partly by its own internal mechanism working a screw. In 40 seconds it will travel 500 yards, carrying in the head of it a charge — of a full sized torpedo — of some three-quarters of a hundredweight of gun-cotton or dynamite. It seems doubtful whether anything afloat could stand the blast of one of these monsters of the deep. It was one drawback to the efficiency of these torpedoes propelled from tubes lying fixed in the bows of the boat, that the vessel must be running straight for the object of attack. To obviate this disadvantage there is a third tube of similar dimensions mounted in the after part of the boat and, as has already been intimated, capable of being trained in any direction. This can be discharged at an object, and whatever may be the course of the vessel, and even when she is going at full speed. This boat has also a machine-gun set up on what is called the "conning-tower," a small iron citadel, like a magnificent cheese, with slits all round it, in which is the head of the officer in command, the slits affording him an outlook raised a little above the general level of the boat. As these boats are designed to have the largest amount of power packed into the smallest amount of space, even the torpedo-room has to be utilised for some of the crew, who have to swing their hammocks across the little chamber just under the tube. To sleep soundly just under threequarters of a hundredweight of dynamite, with a chance of being disturbed in the night by three-quarters of a hundredweight sent by a neighbour, must, one would think, require a particularly sound nervous system. -Otago Daily Times, 14/8/1885.

A mixed detachment of Wellington Navals and A.C.'s had some practice with the the torpedo boat in the harbour. About dusk the boat was headed at full speed at a hulk, as though to attack it, a torpedo filled with about 121b. of dynamite was boomed out and exploded when within 50 yards. The engineer reversed engines in capital time, and the boat, except a little wash, cleared the effects of the explosion. The boat stood the shock admirably, but the men felt a little queer for a minute or two, this having been their first charge fired, and the largest, perhaps, ever exploded in the Colony in the same manner. The boat headed for home, and the men were dismissed, well satisfied with their practice. -Otago Daily Times, 20/8/1885.

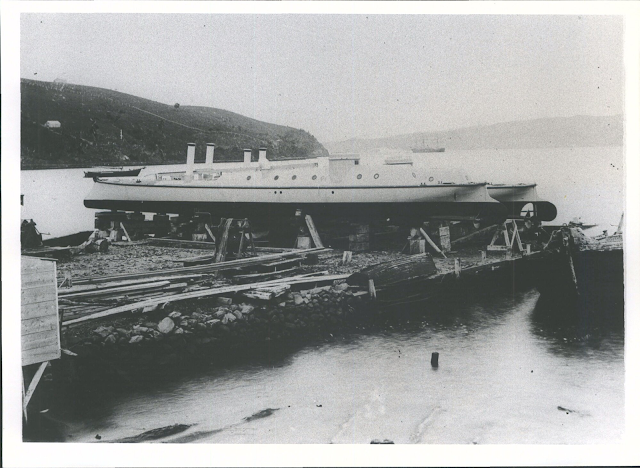

The torpedo boat which has been hauled up on the slip in Deborah Bay since her arrival by the Lyttelton in May, 1884, was launched yesterday. Steam was got up this afternoon to try her engines, and her trial trip will take place on Thursday next. -Evening Star, 16/3/1886.

INTERPROVINCIAL

DUNEDIN. March 16. An attempt was made by Mr Ward, the torpedo instructor, to try a torpedo boat which has been lying on the slip at Port Chalmers for nearly two years, but something went wrong, and the trial had to be postponed. -North Otago Times, 17/3/1886.

SHIPPING

A trial trip of the torpedo-boat was made yesterday. From Deborah Bay to the Jetty street wharf, a distance of about ten miles, was done under very easy steam. In thirty-two minutes, and from town to the Port against a head wind and adverse tide in forty minutes. She also made a run to the Heads against a fresh wind and confused sea, displaying excellent sea qualities. Her boilers had a pressure of 901b to the square inch, and the engines averaged 250 revolutions per minute. Though the conditions were unfavorable - the machinery having been dormant for years, and an inferior coal was used - the trial is considered to have been thoroughly satisfactory. The vessel is to be fitted with appliances for the Whitehead torpedo. Mr Ward, the torpedo instructor, was in charge, and was accompanied by Major Goring, and Messrs Hackworth and Chamberlain, of the Customs. -Evening Star, 18/3/1886.

THE NEW ZEALAND FLEET.

(Lyttelton Times.)

Were it not that serious considerations are so deeply involved, the report which we published the other morning of Admiral Scott's very original little trip round the harbour in a rusty torpedo-boat might well call up a broad grin on the face of everyone who read it. The visit of inspection was sorely needed, and if the Admiral can only give a touch of sarcasm to the report of his visit, with which he will naturally furnish the Government, it should make exceedingly pleasant reading for those inclined to enjoy humour at the expense of the powers that be. The whole affair has its comical side. In due state the Admiral travels up from Dunedin, prepared, no doubt — as most inspecting officers on a first visit are prepared — to be agreeable all round. On Saturday morning he intimates that he will inspect the torpedo launch that day. "Very sorry, sir," is the reply of the commanding officer, "quite out of the question: impossible to get the vessel off the slip to-day; there are waves fully 18in high running." "Would it be equally convenient on Monday — weather permitting, of course?" On Monday the trip is made. The Admiral, like the intelligent baby, soon "begins to take notice." Instead of reeling off her 16 or 17 knots, the boat can only manage the pace of a good passenger launch. Instead of apple-pie order and engines working like extra-fine clockwork, there is rust and dirt everywhere and jerking and grinding. There is priming, there is water blown off that runs down the deck in a red, muddy stream. In a little while the whole thing comes nearly to a standstill, and a man begins to haul saltwater inboard with a bucket to fill the tank. The spar is run in and out, but it is plain that the men are by no means adepts at the work; it does not seem familiar to them. The torpedoboat takes a minute and a-half to turn a complete circle.

Then begin the inquiries. The boat is housed 20 minutes' walk from the town. The slip is so badly made, the nook in which it is placed is so exposed, that, unless in a dead calm and with a splendid rise of tide, it is extremely dangerous to get her off or extremely difficult to get her up. She is brought out, say, four times a year, and drills in her do not help to earn capitation for the gallant Navals, so they cannot afford to waste their time in torpedo practice. There is no engineer belonging to her.and it depends upon the goodwill of the Harbour Board whether one can be secured even when the Admiral comes up to give an eye to that first line of defence of which he is so enthusiastic an advocate. If the torpedo boat is meant to make an impression and not to make oxide of iron, would it not be well for Government to employ an engineer regularly to look after her? Having imported some of the costliest machinery, it is very false economy to let it spoil from parsimonious motives. A trip about the harbour costs, we are advised, from thirty shillings to two pounds. Surely it would not overstrain the resources of the Defence Department to pass vouchers for that amount every month, or even every fortnight, if by so doing the little vessel could be kept in efficient working order. As to the question of drills, that is part and parcel of what we have urged before in these columns: If the Volunteer system of this Colony is not a sham, Volunteers must be taught their trade effectually. -Otago Daily Times, 3/4/1886.

HARBOR BOARD.

The fortnightly meeting of the Harbor Board was held this afternoon. present - Messrs N. V. A. Wales (chairman), A. H. Ross, A. Thomson, J. f. Mackerras Law, J. Hislop, J. A. D. Adams, H. Gourley, J. B. Thomson, and General Fulton.

A letter was received from Rear-admiral Scott stating that he had been directed to make every necessary arrangement for carrying out the naval part of the sham attack on Oamaru at Easter, and he hoped that the Board would aid in rendering the Volunteer gathering a success by allowing one of their steamers to convey the torpedo boat from Port Chalmers to Oamaru, with Guns and ammunition. The steamer, if sent, would add to the value of the manoeuvres were she to be associated with the Hinemoa and Ellen Ballance in the attack. A telegram was received from Colonel Whitmore thanking the Board for the loan of the launch Reynolds, and expressing the opinion that the Otago Volunteers would be much encouraged if the members of the Board could attend at the display. The Board generally were favorable to granting Admiral Scott’s request, but, as they had no power to give the use of their plant gratuitously, it was resolved to grant the use of the Koputai, if the expense for coal and labor is paid for. Several applications for the position of inspector of works were received and referred to the Works Committee for report. -Evening Star, 8/4/1886.

THE EASTER REVIEW. (abridged)

All last evening the town was astir. The mustering of the local volunteers, supplemented by the district companies, attracted much attention, and quite a crowd of townspeople turned out to watch the departure of the volunteers to camp. When on parade, the camp commandant, Major Sumpter, detailed guards and pickets for duty during the night, and guards of honor for the reception of visitors were also appointed by the Major.

The torpedo boat under the charge of Commandant Goldie arrived here yesterday afternoon at 5 o'clock. She cleared Otago Heads at 11 a.m., and made the tun in six hours. As there was a sea running from the N.E. Captain Goldie deemed it not advisable to wait for the Reynolds, which was to convoy the torpedo boat. He took a clear course outside Shag Reef, and arrived two hours before the Reynolds. The engines were only going at half-speed for nearly three quarters of the way. She behaved herself beautifully, and Captain Goldie is loud in his praise of the going capabilities of the boat. She proved herself fit to cover 17 knots an hour. With such power of speed the torpedo boat will doubtless take up a prominent part in the naval demonstration. -North Otago Times, 23/4/1886.

NAVAL DEMONSTRATION.

The plans for this have been made with the utmost possible attention to detail by Assistant Adjutant General Captain Hume. The Hinemoa is to be the flag-ship, and the steamers to take part are the Hawea, the Ohau, the Beautiful Star, the Koputai, the Plucky, the Reynolds, and the torpedo boat. Towards the end of the attack on Oamaru by these vessels with the respective naval corps aboard, the order is that heavy firing shall take place from the town. The vessels are to reply, firing fast. Then the torpedo boat comes into action and disables the Reynolds. The two guard boats are driven off by troops from the shore, and are defeated; the mines explode, disabling one of the squadron, and the whole of the steamers retreat much shattered. Then the victory is won. Oamaru is saved. Loud and long cheers burst from the spectators, and the bands begin to play. If these orders by Captain Hume are acted out in their entirety, undoubtedly this demonstration will prove the most stirring spectacle of the kind ever witnessed in New Zealand. -North Otago Times, 24/4/1886.

THE VOLUNTEER ENCAMPMENT

THE NAVAL ATTACK (excerpt)

The fire concentrated on the boats was so heavy that they hesitated a moment when the reserves of the Canterbury Brigade were brought up and came also into conflict, the effect being terrific. At this instant, too, the torpedo boat, with Captain Goldie on board rushed at the Reynolds and exploded her torpedo, on which she surrendered being supposed to be disabled. The flotilla of boats thereupon made off, retreating to the fleet without further casualty, but pursued by the torpedo boat which took this occasion to make an exhibition of her speed and power of turning in and out in a small circle. The guns meanwhile continued to pour a hot fire on the hostile squadron, which replied as warmly, but on recovering his boats the Admiral once more withdrew, and the fire from the shore ceased. -Oamaru Mail, 26/3/1886.

Full story of the attack here.

TELEGRAMS

Oamaru, April 29. The torpedo boat is still detained here through bad weather. -Otago Daily Times, 30/4/1886.

The torpedo boat, after waiting for some days in port for favorable weather to leave for Port Chalmers, got away this afternoon, she was convoyed by the steamer Beautiful Star. -Oamaru Mail, 5/5/1886.

The civil war which a correspondent recently informed us was in progress in Kakanui is occasioning a good deal of interest amongst those more immediately engaged. No lives have been lost to the cause of the closed road, but at this early period of operations it might be hazardous to guess at what the ultimate result will be. From the following question asked by a "Kakanui Resident" it is evident that active preparations are being made to take the field, the "closed road," or whatever the opposing forces can lay their hands on: "Can you inform me whether there is any ammunition left over from the recent naval engagement at Oamaru that would be available for the civil war at Kakanui, and upon what terms the torpedo boat could be hired." If our correspondent thinks noise would settle the dispute, the kind of ammunition used at the naval attack would prove the very thing that is required — it was blank, and it could probably be procured on application to Major Sumpter. Our correspondent forgets to state whether the torpedo boat is to be used on the land or on the river and if on the land whether the belligerents would provide their own horses to draw it around with the army. We offer the suggestion that a big drum or a pair of cymbals would be appropriate weapons to take the field with. They would be more in keeping with the blank ammunition. -North Otago Times, 17/5/1886.

THE DEFENCE WORKS (excerpt)

Steady progress has been made in connection with the defence works, and a good deal of work has been done and is still in progress in connection with the defence of the port of Otago and this city. The central battery, which has been built on the sandhills, a little to the south of the Grand Pacific Hotel, is nearly completed. The foundation consists of bluegum planking, on which are laid transversely 401b rails 12in apart. On this there is a bed of concrete, and that forms the groundwork of the fortification. The gunpits are completed with the exception of the pivots, and the connecting gallery is built and covered in. Guns of somewhat smaller calibre but greater effective power than those at Lawyer's Head and St. Clair will be mounted in this battery — the guns being 6in, breechloaders, with iron shields. A magazine and barracks are to be built, and the foundations for these structures have been laid. The palisading round the fort is finished, and so are the slopes, so that altogether a very large amount of work has been done.

The batteries at Lawyer's Head and St. Clair are not yet finished, as another 8-ton gun has to be placed in position at each fort. Both guns will be breechloaders.

At Taiaroa Head a 7-ton gun, with a seaward range, has been mounted in the vicinity of the lighthouse, and a pit has been excavated for a 6in breechloader similar to the ones that are to be placed in the central battery at the Ocean Beach. A parapet wall is being built at the rear of the batteries at the heads, so that it could be lined with infantry to protect the guns in the event of an assault from the shore.

Work at the sub-marine mining station at Deborah Bay is also proceeding. A mining shed, torpedo shed, barracks, cable tank, test pit, workshop and office are now in hand, and will soon be completed, and the needful reclamation it being carried on. The building of a slip for the torpedo boat is also contemplated. -Otago Daily Times, 23/2/1887.

DUNEDIN GOSSIP (excerpt)

Our "only general" has inspected our Volunteers ere he retires to private life, and has given them his blessing. The muster was good, and they undoubtedly made a splendid show, quite justifying the compliment on their physique. The movement is at present exciting some interest in view of the retrenchment policy, and great curiosity is felt as to what direction it will take. No one denies for a moment that the force would fight, and fight bravely and desperately for home, but all the same they can only he looked upon as a last resort. They could not be expected to be ready at every moment, whether day or night, to ward off the attack of a hostile cruiser, nor does the artillery branch possess the requisite skill to work the big guns which are mounted to keep the foe at a respectful distance. The service the Volunteers would render would be against a force landed upon our shores and against such a remote contingency the precaution is too great and too expensive. Truth to say there is very considerable doubt whether the permanent force licked into presentable shape by the late government are much superior to the Volunteers, a doubt largely increased by General Shaw's opinion. With all the heavy expenditure on forts, guns, and torpedo boats at the principal ports, many think we are but little better off than we were three years ago. It is even said we are worse, for while we were then unprotected, we now make a pretence of being defended, and would fare worse in consequence. With incomplete forts, partially mounted guns, and a torpedo boat whose plates are said to have been eaten away by rust, there are grounds for believing that an enterprising enemy would make short work of us. -Cromwell Argus, 7/2/1888.

The torpedo demonstration was one of the principal attractions of the day and was thoroughly successful. The only drawback was that there was nothing to attract attention to it, and consequently a number must have missed it, since it occupied only a few seconds of time. The boat which was to be destroyed had been bought for the purpose. Two masts were rigged in it, and to make the thing more realistic, dummy men were placed on board the doomed vessel. Promptly at two o’clock, and while the attention of most spectators was held by the finish of a rowing race, the noise of an explosion was heard, and a large column of water was seen to rise in the air, a white frothing mass. When the commotion subsided nothing but fragments of the boat could be seen floating on the discolored foam. This demonstration was undertaken by Lieutenant Lodder, the torpedo instructor, assisted by the Torpedo Corps and Navals. -Evening Star, 27/12/1888.

A special feature in connection with the forthcoming Dunedin Regatta, to be held on Saturday, February 2, will be a grand submarine mine explosion and a display of the capabilities of the torpedo boat, which will be carried out by the Torpedo Corps, under the direction of Lieutenant Lodder. As the majority of the Dunedin public have never witnessed this modern war vessel under steam, a large crowd should be attracted to watch the various evolutions. -Otago Daily Times, 23/1/1889.

THE DUNEDIN REGATTA (excerpt)

The Submarine explosion conducted by the Torpedo Corps and Dunedin Navals, under the direction of Lieutenant Lodder, was carried out most successfully. The craft doomed to destruction was moored about 200yds from the Rotorua, and at a given signal the engine of destruction was fired. The result was more than was anticipated by the spectators, for an immense column of water was thrown into the air to a height of about 200 ft, carrying with it the debris of the boat, which was scattered over the after part of the Rotorua and on to the wharf. The torpedo boat manoeuvres under the superintendence of Lieutenant Lodder was also an interesting spectacle. The torpedo was affixed to a spar running out from the bow of the boat. She then forged ahead, the spar was depressed so that the torpedo was submerged, and the explosion followed, the boat backing rapidly away from the disturbed water. -Otago Daily Times, 4/2/1889.

SHIPPING

The torpedo boat no. 169 steamed up from Port Chalmers yesterday forenoon, and after embarking Captain Falconer, Mr Blackwood (Government inspector of machinery), and others ran down to Deborah Bay, returning to Dunedin in excellent time. The little vessel (already reported upon by us) appeared in perfect order. -Otago Daily Times, 18/4/1890.

OUR VOLUNTEERS.

The submarine and torpedo division of the Port Chalmers Naval Artillery mustered on Saturday afternoon at the Bowen pier and embarked in the defence steamer Gordon, which conveyed them to the torpedo depot at Deborah Bay, where they were instructed in the laying out of mines, &c. in the harbour. Chief P.O. Pacey and P.O. Sharpe, of the Torpedo Corps, were the instructors, and expressed themselves highly pleased at the manner in which the various detachments went about their work. -Otago Daily Times, 25/8/1890.

SHIPPING TELEGRAMS

The Government torpedo boat, No. 161, made a couple of trips up and down the harbour yesterday. Captain Falconer was present, and amongst the visitors were Captains Edwards and Tate, Messrs J. Morgan, C. Macandrew and others. On both occasions the little boat behaved admirably, and Chief Petty-officer Pacey, with Petty-officer Sharpe were congratulated on the admirable manner in which everything went off. -Otago Daily Times, 9/10/1890.

SHIPPING TELEGRAMS

The Government torpedo boat, No. 161, made a couple of trips up and down the harbour yesterday. Captain Falconer was present, and amongst the visitors were Captains Edwards and Tate, Messrs J. Morgan, C. Macandrew and others. On both occasions the little boat behaved admirably, and Chief Petty-officer Pacey, with Petty-officer Sharpe were congratulated on the admirable manner in which everything went off. -Otago Daily Times, 9/10/1890.

LATE ADVERTISEMENTS

DISTRICT ORDER, Militia and Volunteer Office, Dunedin, March 9, 1891.

The Port Chalmers Naval Artillery Volunteers will furnish a Firing Party of 13 Rank and File under command of a First-class Petty Officer to attend the Funeral of the late Torpedoman W. Densem, of the Torpedo Corps, Permanent Militia. The Party to Parade at the Garrison Hall, Port Chalmers, at 3.45 p.m. on WEDNESDAY, 11th inst. The Port Chalmers Band is requested to attend, and Officers and Members of Volunteer Corps in the district are invited to assemble at the Dunedin Railway Station at 2.15 p.m.

H. W. WEBB, Lieut.-colonel, Commanding District.

___________________________________________________

THE MEMBERS of L BATTERY, N.Z.A.V., are requested to Parade at the Garrison Hall, Port Chalmers, on WEDNESDAY, 11th Inst, at 3.45 p.m. sharp, to attend the Funeral of the late W. Densem, Torpedo Corps.

Full dress, white gloves, and side arms.

W. J. WATERS, Captain.

____________________________________________________

PORT CHALMERS NAVAL ARTILLERY VOLUNTEERS.

THE COMPANY will Parade at the Garrison Hall on WEDNESDAY, the 11th inst., at 3.45 p.m. in order to attend the Funeral of the late Torpedoman William Densem, of the Permanent Torpedo Corps. Uniform and side arms only.

T. J. THOMSON, Capt., Port Chalmers Naval Volunteers.

Naval Orderly Room, Port Chalmers, March 10,1891. -Evening Star, 10/3/1891.

AN EXPLOSION AT THE FORTS.

Shortly after 11 am yesterday week an explosion of gun cotton occurred at Shelly Bay, which seriously injured five members of the Torpedo Corps. It appears that the unfortunate men, whose names are Ross, Densem, Cornwall. Goldie, and McCallum, were engaged filling gun cotton cartridges in the smithy at Shelly Bay, when one of the cans exploded, the concussion from which had the effect of exploding seven others already filled and stacked in the shed. As soon as the accident occurred, a message was sent by telephone for a doctor, and Dr Cahill, accompanied by the Hon Mr Seddon, went across in the Ellen Ballance to the scene of the accident. The injury to the unfortunate man Ross was found to be so serious that his depositions were taken. It appears that Ross was filling up tins which held about 51bs of gun cotton. To make it clear it may be stated that after placing the gun cotton in the tins about an inch of space is left at the top which is filled with ashes, and then the lid is soldered on. When the explosion occurred Ross was in the act of soldering one of these tins. The explosion was so terrific that it drove Ross to the other end of the shed, and he landed on the other seven tins, which then immediately exploded and blew the unfortunate man back to the spot where he was first at work. The poor fellow was horribly disfigured. His whole body was more or less scorched, the skin was burnt off his face, arms, and legs. He had cuts on both his hips, legs, and lip, and a terrible wound in his abdomen. The other men were badly burnt by being driven by the force of the concussion against the machinery in the building. As to the cause of the accident there are two theories, one is that the ashes which had been used to fill up the tins contained a live ember; the other is that the heat of the soldering iron ignited the cotton. It may be mentioned that the work of filling these tins was carried on within seven feet of the smithy fire. Goldie and McCallum were brought over at 5 o’clock, the former being taken to the A.C. Depot, and McCallum to his friends.

The man Cornwall as soon as he realised what had happened rushed out into the water to extinguish his burning clothes.

Captain Falconer had only left the shed a minute or so before the explosion to attend to some clerical work, and was in the act of returning when the accident occurred.

DEATH OF ROSS AND DENSEM

ROSS’ DEPOSITIONS.

We regret to say that two of the torpedo men who were injured by the explosion which took place at Shelly Bay on Thursday succumbed to their injuries. Ross died on Friday evening at half-past 5 o’clock, and Densem at a few minutes past 9. Ross was 35 years of age, a blacksmith by trade, and was at one time in the employ of Messrs Luke and Sons, of Te Aro Foundry. He was always considered a good tradesman, and after joining the Torpedo Corps about five years ago, Captain Falconer selected him to take charge of the blacksmith’s shop connected with the station. Densem was a single man.

The following is a copy of Ross’ depositions, taken at the request of Mr Seddon:

On being asked how the explosion occurred, Ross said — I was soldering the lid of one of the tin cases, which was filled with guncotton — the round tin cases I mean — when it exploded. I recollect what followed. The explosion blew me across the workshop. That was the first charge, and it blew me right on to two or three other tins that were standing there. They began to explode just as I landed on them, and they blew me back again — the same way as I came. I was crawling out when the ones on the end bench were exploding.

Mr Seddon — How do you account for them going off?

Ross — The heat of the solder bolt did it.

Mr Seddon — Did you put any ashes on top of the gun cotton?

Ross — George Goldie put them on.

Mr Seddon — Where did he get them from?

Ross — Off the old forge. They were cool enough.

Mr Seddon — How far off the fire were you when you were soldering up?

Ross — About seven or eight feet

Mr Seddon — Was the lid on the tin?

Ross — Yes. I was just putting the finishing touch on the top when it exploded in my bands.

Mr Seddon —Then how did the heat from the soldering iron affect the gun cotton?

Ross — I don’t know. I had a small bolt. I cannot say how the heat from it got at the gun cotton.

Mr Seddon: Did you say that Goldie took the ashes from the old forge?

Ross: Yes.

Mr Seddon: For that particular tin?

Ross: Yes; he took them from the old forge, and put them on top of the gun cotton.

Mr Seddon: Was there any chance of the fire from the forge getting at the gun cotton?

Ross: No.

Mr Seddon: None whatever?

Ross: No.

Mr Seddon: Do you remember how many of them you had soldered before?

Ross: I was on about the second from the last half. There were eight, and I had done five.

Mr Seddon: Had you been doing this kind of work before?

Ross: Yes. George Goldie and the Captain made up the last lot. By the Captain I mean Captain Falconer. It was no fault of Goldie’s, as the tins were standing with the ashes in them for some time before I touched them. If there had been any fire in the ashes they would have exploded before I touched them. I never liked the job of soldering the tins, for I believed it to be dangerous. This I have said to those who were working with me. I have never said anything to Captain Falconer about it being dangerous. Yes; I did ask him once about it. He said there was no danger if it was properly and carefully done. The statement that two trained nurses were sent over during Friday afternoon is incorrect. The Ellen Ballance was waiting a considerable time at the breastwork to convey them to the Peninsula, but no one seemed to know whom to apply to for the necessary authority to engage the nurses. The Hospital authorities said they had no power without a written order from the Trustees, and none of these gentlemen could be found. Owing to the delay caused by red-tape no nurses had been sent over up to 8 o’clock.

Four tobacco pipes were picked up in the smithy Friday morning, and it was suggested that a spark from a pipe might have caused the explosion. Captain Falconer inclines to this belief rather than to the theory that hot ashes had anything to do with it. Smoking was forbidden during such work, but he believes that the men were violating this regulation when the accident happened.

ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE INQUEST.

THE FUNERAL OF ROSS.

According to arrangement, the Coroner Mr Robinson, R.M., and the jury, consisting of Messrs C. Gamble (foreman), W. Christie, J. Stock, Wm. Mackay, Alex. Watt, and C. T. Williams, left the Railway Wharf in the Ellen Ballance on Saturday afternoon, in order to proceed to the scene of the recent accident. Inspector Thomson, Sergeant Iviely, Colonel Humfrey, Captain Falconer, and Dr Cahill were also of the party. On arrival, the jury viewed the bodies of Ross and Densem, and a careful examination of the premises was made. Captain Falconer igniting a quantity off gun-cotton, to show how the explosion took place. After some discussion, it was decided to adjourn the inquest until Monday next, the 16th instant, it being anticipated that Cornwall will have sufficiently recovered by that time to enable him to give evidence.

An enormous concourse of people assembled in the vicinity of the Railway Wharf on Sunday afternoon, and there could not have been less than six thousand present. The following was the parade state of the various corps that followed the coffin of the late William Ross:

Permanent Artillery (Major Messenger) 71

Wellington Navals (Captain Duncan) ... 88

Petone Navals (Lieutenant Davie) ... 40

Wellington City Rifles (Lieutenant Wilson) ... ... ...30

Wellington Guards (Captain Macintosh) 48

Wellington Rifles (Captain Hobday) ... 44

Total ... ... ... ... 316

A few minutes after 3 o'clock the Ellen Ballance was seen proceeding slowly from the fort, the steamer having on board the coffin and a number of the Torpedo Corps, who were deputed to act as pall-bearers. The Volunteers were drawn up in line, and the coffin being placed on one of the gun carriages belonging to the D Battery, the mournful procession proceeded on its way, headed by the Garrison Band playing “The Dead March in Saul,” the firing party of the Permanent Artillery following next with their arms reversed. The cortege marched slowly along till the Sydney street entrance to the Cemetery was reached, where Mr H. Gaby, who was to read the burial service, was in attendance. The coffin was removed from the gun carriage and placed in the charge of the pall bearers, who carried it to the place of burial. Here a large crowd had gathered together, and after Mr Gaby had read the Church of England Burial Service in a most impressive manner, the body was lowered into the grave, and when the firing party had fired three volleys the assemblage dispersed. All the vessels in port had their flags flying half mast both on Saturday and Sunday.

Densem’s body was conveyed to Dunedin, where his people reside, on Monday. He was a young man of twenty years of age, and the son of Captain Densem, the master of the Government steamer Gordon, stationed at that port. The deceased was most popular among his comrades, and was generally considered one of the smartest men in the corps.

Cornwall is, according to latest reports, progressing favourably, and Dr Cahill, who paid two visits to the fort on Sunday, considers that there are good hopes of his recovery. The injured man is about 28 years of age, and is the son of Captain Cornwall, late of the 75th Regiment, who is a resident of New Plymouth.

The life of the late William Ross whose real name, however, was Walter Horrocks Heighton, was insured for £200 in the Mutual Life Association of Australasia. It may be explained in reference to the change of name, that Ross was adopted as a nom de theatre by the deceased when he was following the profession of an actor, and it was by this name that he was universally known among his companions. -NZ Mail, 13/3/1891.

THE GUN COTTON EXPLOSION AT SHELLY BAY.

THE INQUEST.

The inquest on the bodies of Walter Horrocks Heighton (better known as William Ross) and William Densem, who died from the effect of injuries sustained at the gun cotton explosion in Shelly Bay last Thursday week, was resumed in the common jury room at 10 a.m. to-day before Mr. H. W. Robinson, District Coroner, and the following jurymen: — Messrs. O. Gamble (Foreman), W. Christie, J. Stick, W. Mackay, Alex. Watt, and T. Williams. Mr. Skerrett appeared for Capt. Falconer, the officer in charge of the torpedo station, Mr. Jellicoe for Mrs. Heighten, and Mr. Golly on behalf of the Government.

The inquest on the bodies of Walter Horrocks Heighton (better known as William Ross) and William Densem, who died from the effect of injuries sustained at the gun cotton explosion in Shelly Bay last Thursday week, was resumed in the common jury room at 10 a.m. to-day before Mr. H. W. Robinson, District Coroner, and the following jurymen: — Messrs. O. Gamble (Foreman), W. Christie, J. Stick, W. Mackay, Alex. Watt, and T. Williams. Mr. Skerrett appeared for Capt. Falconer, the officer in charge of the torpedo station, Mr. Jellicoe for Mrs. Heighten, and Mr. Golly on behalf of the Government.

Colonel Humfrey, Under-Secretary for Defence; Major Messenger, the officer in charge of the Permanent Militia; Mr. Bell, Engineer for Defences; and Captain Cornwall, of Taranaki, and Mr. Goldie, of Dunedin, respective, fathers of two of the injured survivors, were also present.

Inspector Thomson represented the police, but the enquiry was conducted by Mr. Gully.

The first witness was Samuel John Espenett, a petty officer in the Torpedo Corps, who deposed that he was at the Shelly Bay station on the 5th inst. A few minutes before 11 a.m. he was in the kitchen. About an hour previously he was engaged in giving Third-class Torpedoman McCallum some instruction in the smith's shop. Heighton (Boss) and Densem were also there, but witness had nothing to do with their work. About 10 minutes to 11, when he was in the kitchen, some little distance from the smith's shop, he heard an explosion, and ran out. He saw two of the men running down to the water from the direction of the smith's shop. Between the beach and the shop there was a space of about 100 yards. The men, whom he found to be McCallum and Second-class Torpedo-man Cornwall, ran into the water. Someone went to Cornwall's assistance, and witness also helped. Cornwall was put into his bunk, and kept oiled until the doctor arrived. The day after the explosion witness found a tobacco pipe near the empty mines, between the sea and the smithy. He did not know whose pipe it was, but he had been told that it was Cornwall's.

Mr. Jellicoe objected to the witness giving evidence as to something that he had been told.

Mr. Skerrett argued, however, that evidence of the kind was perfectly admissible.

Mr. Gully said he had a reason for getting the evidence on the depositions. Cornwall was still ill, and it was not unlikely that he would be unfit to be examined for some time to come. Two witnesses who were in the smith's forge would be examined as to the pipe, and it was possible that the jury might consider it unnecessary to wait until Cornwall could attend. It was therefore desirable that evidence concerning the pipe should now be taken.

Mr. Jellicoe pressed his objection to the witness giving hearsay evidence. The enquiry, he pointed out, was a very serious one, and as it was sought to throw the responsibility of the accident upon the men engaged in the smithy, the Coroner should be careful in not admitting hearsay evidence.

Mr. Skerrett denied that there was any intention to throw the blame upon the men, and charged Mr. Jellicoe with attempting to play a role which had long ago become stale, flat, and unprofitable.

After a heated discussion between Messrs. Jellicoe and Skerrett, his Worship said that if they did not cease squabbling he should have to request them to leave the Court.

The Coroner decided to accept the evidence regarding the pipe as hearsay evidence.

The witness, continuing, said he had shown the pipe to several persons, who told him that they thought it belonged to Cornwall.

Cross-examined by Mr. Skerrett, the witness said that he had been in the service for 12 years, and had some experience of explosives, including gun cotton. There was a written order against smoking, in the smith's shop and other places at Shelly Bay. He had known of cases where men had beep brought before Captain Falconer and reprimanded on a charge of smoking.

Mr. Jellicoe objected to the last question being answered, and further wrangling took place between Mr. Skerrett and Mr. Jellicoe, whereupon Mr. Gully suggested that in order to allow the enquiry to proceed, his two learned friends should be requested to retire.

His Worship ruled that the question was admissible, and the question was answered as above stated.

In reply to further questions by Mr. Skerrett, witness stated that he had assisted at the filling of primers or canisters for exploding gun cotton. These primers were made by the men, tin or copper being the material used. They were loaded with a certain quantity of dry cotton, which was fired with a detonator. The last primers he assisted to fill were filled about nine months ago. There was a written order that the primers were to be filled in the mining shed. He assisted Captain Falconer at the filling of the primers nine months ago. After those particular primers were filled and the lids soldered on they were placed outside the smithy. .

Mr. Jellicoe objected to the witness answering a question as to certain experiments made by Captain Falconer since the accident, but his Worship ruled against him.

The witness, continuing his evidence, said that Captain Falconer made a fire in the open air, placed a flat bit of tin on top, and on this he put a lump of gun cotton. The gun cotton ignited, and Captain Falconer tried to take the tin off with his hands, but it was too hot to hold. Another piece of gun cotton was put on the tin, and it ignited; but a third piece did not ignite, although the tin was still too hot to hold. Another experiment was made. A soldering iron was made red hot, and some hard solder was melted with it. The soldering iron was then placed beneath the tin plate, and some gun cotton was put on the plate, but the cotton did not ignite. The tin plate rested on the hot iron. Hard solder was easier to melt than soft solder. Molten solder was afterwards allowed to run on to the gun cotton, but the latter did not ignite. Heighton was in charge of the smith's shop, and his instructions were not to in any way interfere with the men engaged in loading the primers. Captain Falconer was a strict disciplinarian.

By Mr. Jellicoe — The gun cotton placed on the tin plate was a very small piece and was unconfined. A piece of dry gun cotton lit in the ordinary way would burn away with a fierce flame. If the same piece of gun cotton was confined and set on fire it would explode. The thicker the primer the greater the explosion. Of course it would not do to have too thick a case. He was surprised to find that the molten solder did not ignite the gun cotton during the experiments at Shelly Bay the other day.

Mr. Jellicoe — Now, suppose that the same quantity of hot solder had found its way into confined gun cotton in a case, would you have expected to find it ignite the gun cotton?

Witness — No; I should not. The witness went an to say that if the question had been put to him before the recent experiments, he would have answered it in the affirmative, and not in the negative, as he now did. He was of opinion that there was no more danger of an explosion from confined gun cotton into which hot solder had been dropped than from unconfined dry gun cotton to which hot solder had been applied. His opinion was that dry gun cotton would ignite at 300 or 400 degrees Fahrenheit. He did not know at what temperature hard solder would melt, nor could he say the temperature of the hot soldering iron on the piece of the tin plate when heated. When he was in the smithy, before the explosion took place, he did not notice any small pieces of gun cotton. Heighton and Densem were at the bench near the forge just before the explosion. The gun cotton was in charge of the storekeeper.

Mr. Jellicoe — Do you consider that a smithy is a safe place for filling primers?

Witness — Yes, if there is a screen. There is a screen in the smithy. In reply to other questions by Mr. Jellicoe, the witness said that when he went into the smithy before the explosion took place, he understood Heighten and Densem were finishing the primers, which had been filled in another shed.

Mr. Gully complained that a great deal of time was being wasted in asking questions which ought to be put to the scientific witnesses who were to be called.

Mr. Jellicoe contended that it was necessary in the interests of all concerned that the enquiry should be a full and searching one, and his Worship allowed the examination to proceed.

Replying to another question by Mr. Jellicoe, Petty Officer Espenett said that when he assisted Captain Falconer at filling the primers nine months ago, he considered the work perfectly safe.

Dr. Cahill deposed that on the 5th inst. he was called over to Shelly Bay, and reached there a few minutes after noon. He attended several men who had been injured by an explosion of gun cotton. He first saw Densem, then Cornwall, and afterwards Heighton (Ross.) Densem was lying on a stretcher on the verandah in front of the barrack room, while Cornwall and Heighton were on camp beds inside the barrack room. Densem was found to be suffering from shock. There were also wounds as if he had been bit by some-thing, or had struck against something, and he was also badly burned. Witness administered morphia and stimulants, and Densem went off to sleep. The others were then similarly treated, after which the wounds on each were dressed. Heighton was also suffering from shock, the result of burns and wounds. Densem's death was caused by shock and effusion of the brain. Heighton died about 5 o'clock on the evening after the accident, also from shock and effusion of the brain. Densem died about 8.30 or 9 the same night. Witness was still attending to Cornwall. He had also attended to McCallum's injuries, which were not serious.

By Mr. Skerrett — Heighton was very much burnt about the face and head, and had a jagged wound on the upper lip below the nose. To have caused the wound on the upper lip Heighten must have been bit by something. Witness was present at the recent experiments in Shelly Bay, and considered that P.O. Espenett had given a very fair description. The molten solder was allowed to drop on the gun cotton from a height of three or four inches, but the cotton was not ignited.

Corporal Wall gave evidence that on the 5th of the present month he was talking to Corporal Nelson in one of the sheds, when they heard an explosion. On looking out he saw a flame inside the smithy. There was a large orange yellow flame, such a flame as would be caused by the ignition of gun cotton. As he rushed towards the door of the smithy he heard a succession of small reports, and then one louder than the others. The last report occurred as he was opposite the smithy door. When he arrived at the door a large volume of smoke and flame was coming out. Heighton then rushed out with his clothes alight and his arms in the air, and he was crying. Witness and Corporal Nelson caught hold of him, rolled him on the ground, and put out the fire. The only words Heighton uttered at the time were "Oh, chaps!" or "Oh, boys!" The poor fellow was taken into the barrack room, and his injuries attended to.

At this stage the enquiry was adjourned for lunch. The examination of Corporal Wall was continued in the R M. Court Chamber shortly after two o'clock. The witness, replying to further questions by Mr. Gully, stated that he picked up the pipe produced in the smith's shop about an hour after the explosion. He found it on a bench on the right-hand side going in.

By Mr. Jellicoe — When he found the pipe the screen on the forge was perfectly open. The screen had not been used a great deal. The last time he saw it used was about three months ago. He saw Captain Falconer about the station on the day of the explosion. He did not see the screen on the forge on the day of the explosion. The first time that day that he went into the smithy was when he rushed in after the explosion took place. He had not a full view of the smithy door from the time of the explosion until he found the pipe. He had been in Shelly Bay every day except Sunday since the explosion. One of his duties was to do clerical work for Captain Falconer. He could not recollect filling up any forms respecting gun cotton. Did not recollect that he filled up some forms respecting gun cotton since the accident, and that some one spoke to him about them. He would swear that. The roof of the smithy was of corrugated iron, and the walls were eight or ten feet high. The chimney was of iron. The weather on the day of the explosion was close, and the temperature rather high.

[Left sitting.] -Evening Post, 16/3/1891

VOLUNTEER INTELLIGENCE (excerpt)

A few Saturdays ago the section were shown over the torpedo station at Deborah Bay. Proceeding, from town by the Gordon, they were met by the sergeant-major, who explained the nature of the mines, fuses, etc., the method of fusing and laying, and the various keys, etc., used in connection with the batteries for firing, etc. During the afternoon a considerable charge of gun cotton was fired, which added interest to the proceedings. -Evening Star, 5/6/1897.

TENDERS, addressed to undersigned, will be received up to SATURDAY, 3rd September, for RETUBING BOILER OF TORPEDO BOAT. Specifications can be seen at Torpedo Station. Deborah Bay, and at Central Battery, South Dunedin.

H. O. MORRISON.

Captain commanding permanent Militia, Central Battery, South Dunedin. -Evening Star, 30/8/1898.

LOCAL AND GENERAL

Captain St. L. Moore, R.A., Captain Morrison (Garrison Artillery) and Captain Falconer (Torpedo Corps) have selected sites at Otago Heads for a six inch gun battery, an engine-room for working the electric light and a testroom for the Torpedo Corps, whose quarters are to be removed from Deborah Bay to the Heads. -NZ Times, 23/1/1902.

The Government torpedo boat, after being thoroughly cleaned and repainted on Isbister's slip, was hauled into the stream yesterday. -Otago Daily Times, 13/6/1903

After a career of twenty-two years, most of it spent uneventfully in Deborah Bay, the Government torpedo boat was towed up to Port Chalmers yesterday in preparation for passing into private hands — the hands of the shipbreaker, perhaps. As she went up the bay in tow of the Ellen Ballance members of the Harbor Board, who were on the Plucky, and other spectators on the wharves, watched her with interest, and speculated a little as to her ultimate fate. It may be of interest to mention that the little boat was one of four built for the colony at Chiswick in 1884, and designed to steam 17 knots. So well have her engines been looked after during her stay here that on her last spin in the harbor she just touched 16 knots — this with new boilers, however. Auckland, Wellington, and Lyttelton parted with their torpedo boats some time ago, so that the impending sale here looks like the passing of the last remnant of New Zealand’s navy. A rather interesting point about her would be the position that would arise if a private citizen, purchasing her, became the owner of a vessel of war in his own right. It is understood, however, that the Defence Department will “draw her teeth” prior to disposing of her. None of her torpedo cradles, or any other “business” notion, will go with her when she comes under the hammer. -Evening Star, 6/3/1906.

DEFENCE DEPARTMENT

SALE

TENDERS are invited for the PURCHASE of the S.S. NILE, including Machinery and Equipment, as she now lies at Port Chalmers.

Also for TORPEDO BOAT and Machinery, as she now lies at Port Chalmers. Permission to inspect same will he given on application to the Officer Commanding, Otago Military District. Dunedin.

Ten per cent, to accompany each tender. Any tender not necessarily accepted.

Tenders, in sealed envelopes, to be addressed to "The Under Secretary Defence, Wellington," up to and including WEDNESDAY, 4th April, 1906. Further particulars can be obtained from Officers Commanding Military Districts, Otago, Canterbury, Wellington, or Auckland.

A. W. ROBIN,

Colonel O.C. Otago District.

(For the Under Secretary Defence, N.Z.). -Otago Daily Times, 7/3/1906.

Another defence craft - the torpedo boat - whose existence the public were chiefly aware of on regatta days, is now being broken up on the beach at Deborah Bay after a quarter of a century's service in the Lower Harbor. Her engines are being forwarded to the Canterbury Technical School, and on Saturday her boiler was being taken out. -Evening Star, 8/7/1907.

By Mr. Jellicoe — The gun cotton placed on the tin plate was a very small piece and was unconfined. A piece of dry gun cotton lit in the ordinary way would burn away with a fierce flame. If the same piece of gun cotton was confined and set on fire it would explode. The thicker the primer the greater the explosion. Of course it would not do to have too thick a case. He was surprised to find that the molten solder did not ignite the gun cotton during the experiments at Shelly Bay the other day.

Mr. Jellicoe — Now, suppose that the same quantity of hot solder had found its way into confined gun cotton in a case, would you have expected to find it ignite the gun cotton?

Witness — No; I should not. The witness went an to say that if the question had been put to him before the recent experiments, he would have answered it in the affirmative, and not in the negative, as he now did. He was of opinion that there was no more danger of an explosion from confined gun cotton into which hot solder had been dropped than from unconfined dry gun cotton to which hot solder had been applied. His opinion was that dry gun cotton would ignite at 300 or 400 degrees Fahrenheit. He did not know at what temperature hard solder would melt, nor could he say the temperature of the hot soldering iron on the piece of the tin plate when heated. When he was in the smithy, before the explosion took place, he did not notice any small pieces of gun cotton. Heighton and Densem were at the bench near the forge just before the explosion. The gun cotton was in charge of the storekeeper.

Mr. Jellicoe — Do you consider that a smithy is a safe place for filling primers?

Witness — Yes, if there is a screen. There is a screen in the smithy. In reply to other questions by Mr. Jellicoe, the witness said that when he went into the smithy before the explosion took place, he understood Heighten and Densem were finishing the primers, which had been filled in another shed.

Mr. Gully complained that a great deal of time was being wasted in asking questions which ought to be put to the scientific witnesses who were to be called.

Mr. Jellicoe contended that it was necessary in the interests of all concerned that the enquiry should be a full and searching one, and his Worship allowed the examination to proceed.

Replying to another question by Mr. Jellicoe, Petty Officer Espenett said that when he assisted Captain Falconer at filling the primers nine months ago, he considered the work perfectly safe.

Dr. Cahill deposed that on the 5th inst. he was called over to Shelly Bay, and reached there a few minutes after noon. He attended several men who had been injured by an explosion of gun cotton. He first saw Densem, then Cornwall, and afterwards Heighton (Ross.) Densem was lying on a stretcher on the verandah in front of the barrack room, while Cornwall and Heighton were on camp beds inside the barrack room. Densem was found to be suffering from shock. There were also wounds as if he had been bit by some-thing, or had struck against something, and he was also badly burned. Witness administered morphia and stimulants, and Densem went off to sleep. The others were then similarly treated, after which the wounds on each were dressed. Heighton was also suffering from shock, the result of burns and wounds. Densem's death was caused by shock and effusion of the brain. Heighton died about 5 o'clock on the evening after the accident, also from shock and effusion of the brain. Densem died about 8.30 or 9 the same night. Witness was still attending to Cornwall. He had also attended to McCallum's injuries, which were not serious.

By Mr. Skerrett — Heighton was very much burnt about the face and head, and had a jagged wound on the upper lip below the nose. To have caused the wound on the upper lip Heighten must have been bit by something. Witness was present at the recent experiments in Shelly Bay, and considered that P.O. Espenett had given a very fair description. The molten solder was allowed to drop on the gun cotton from a height of three or four inches, but the cotton was not ignited.

Corporal Wall gave evidence that on the 5th of the present month he was talking to Corporal Nelson in one of the sheds, when they heard an explosion. On looking out he saw a flame inside the smithy. There was a large orange yellow flame, such a flame as would be caused by the ignition of gun cotton. As he rushed towards the door of the smithy he heard a succession of small reports, and then one louder than the others. The last report occurred as he was opposite the smithy door. When he arrived at the door a large volume of smoke and flame was coming out. Heighton then rushed out with his clothes alight and his arms in the air, and he was crying. Witness and Corporal Nelson caught hold of him, rolled him on the ground, and put out the fire. The only words Heighton uttered at the time were "Oh, chaps!" or "Oh, boys!" The poor fellow was taken into the barrack room, and his injuries attended to.

At this stage the enquiry was adjourned for lunch. The examination of Corporal Wall was continued in the R M. Court Chamber shortly after two o'clock. The witness, replying to further questions by Mr. Gully, stated that he picked up the pipe produced in the smith's shop about an hour after the explosion. He found it on a bench on the right-hand side going in.

By Mr. Jellicoe — When he found the pipe the screen on the forge was perfectly open. The screen had not been used a great deal. The last time he saw it used was about three months ago. He saw Captain Falconer about the station on the day of the explosion. He did not see the screen on the forge on the day of the explosion. The first time that day that he went into the smithy was when he rushed in after the explosion took place. He had not a full view of the smithy door from the time of the explosion until he found the pipe. He had been in Shelly Bay every day except Sunday since the explosion. One of his duties was to do clerical work for Captain Falconer. He could not recollect filling up any forms respecting gun cotton. Did not recollect that he filled up some forms respecting gun cotton since the accident, and that some one spoke to him about them. He would swear that. The roof of the smithy was of corrugated iron, and the walls were eight or ten feet high. The chimney was of iron. The weather on the day of the explosion was close, and the temperature rather high.

[Left sitting.] -Evening Post, 16/3/1891

VOLUNTEER INTELLIGENCE (excerpt)

A few Saturdays ago the section were shown over the torpedo station at Deborah Bay. Proceeding, from town by the Gordon, they were met by the sergeant-major, who explained the nature of the mines, fuses, etc., the method of fusing and laying, and the various keys, etc., used in connection with the batteries for firing, etc. During the afternoon a considerable charge of gun cotton was fired, which added interest to the proceedings. -Evening Star, 5/6/1897.

TENDERS, addressed to undersigned, will be received up to SATURDAY, 3rd September, for RETUBING BOILER OF TORPEDO BOAT. Specifications can be seen at Torpedo Station. Deborah Bay, and at Central Battery, South Dunedin.

H. O. MORRISON.

Captain commanding permanent Militia, Central Battery, South Dunedin. -Evening Star, 30/8/1898.

LOCAL AND GENERAL

Captain St. L. Moore, R.A., Captain Morrison (Garrison Artillery) and Captain Falconer (Torpedo Corps) have selected sites at Otago Heads for a six inch gun battery, an engine-room for working the electric light and a testroom for the Torpedo Corps, whose quarters are to be removed from Deborah Bay to the Heads. -NZ Times, 23/1/1902.

The Government torpedo boat, after being thoroughly cleaned and repainted on Isbister's slip, was hauled into the stream yesterday. -Otago Daily Times, 13/6/1903